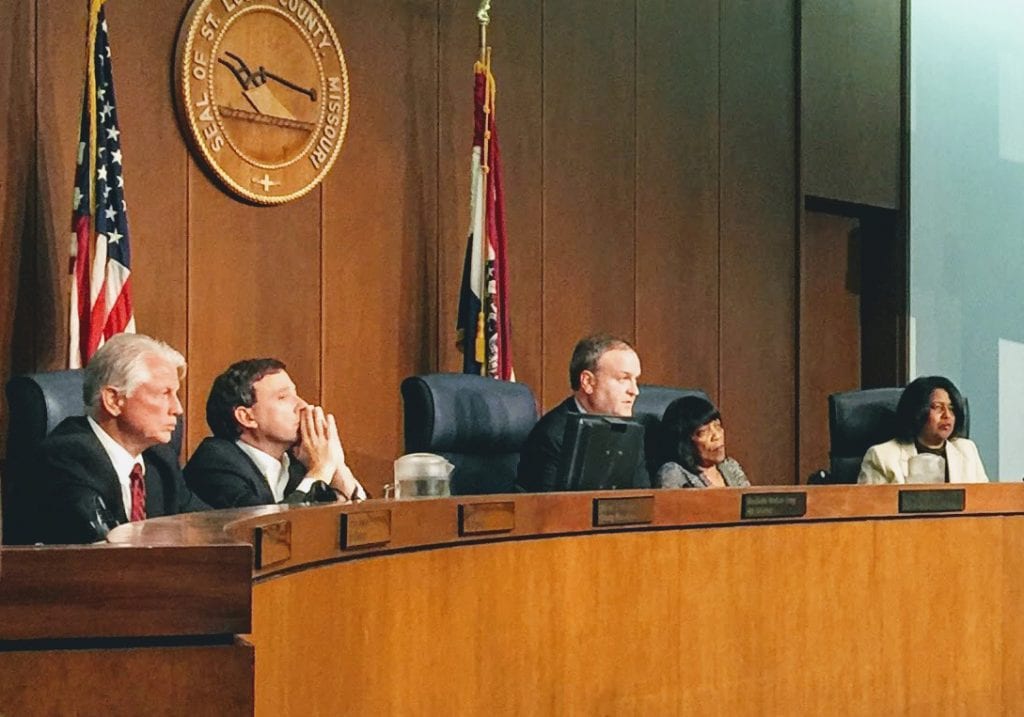

St. Louis County will have to downsize in the future to maintain a balanced budget, but County Executive Steve Stenger said last week that the county’s fiscal condition is not the “financial crisis” that some County Council members are contending.

Council members cite a single paragraph on page 34 of the 362-page, $696 million 2018 county budget as justification for their claims that county finances are out of control.

Chairman Sam Page, D-Creve Coeur, and 6th District Councilman Ernie Trakas, R-Oakville, both took their concerns public after Stenger rolled out the budget Nov. 1, Trakas in an interview with the Call and Page in a letter to Stenger last week.

Budget Director Paul Kreidler noted during a two-hour budget hearing Nov. 8 that the county projects an $18 million operational deficit in 2019 without any additional revenue or cuts. But budgets are tight by choice, Kreidler noted: Stenger, other county executives and the council have chosen not to raise taxes even though they could. The county has 25 cents of wiggle room until it hits its voter-approved property-tax ceiling.

Alternatively, the county can also sell property or roll out money-saving initiatives that Kreidler said were in the works but could not be revealed publicly yet.

Citing Kreidler’s budget-crunching, Page wrote to Stenger Nov. 13, “Now is the time for a plan. The county cannot afford to wait any longer without a plan to address this budget shortfall … This matter is urgent and must be addressed immediately … I invite you to provide the council with an update concerning your plan to address this impending financial crisis.”

The notation in this year’s budget echoes last year’s budget letter from Stenger, along with notes in budgets under former County Executive Charlie Dooley, who led the county for over a decade and through declining revenue in the Great Recession before Stenger defeated him for office in 2014.

Stenger, who is seeking re-election next year, derided Page’s current concern over the budget as “election-year politics” and an echo of Dooley’s attempt to manufacture a crisis in 2011, when the then-county executive proposed closing dozens of county parks to balance the 2012 budget. As council chair, Stenger led a revolt on the council against the cuts and prevented 25 park closures.

“First and foremost, under our administration, county government will not increase taxes or cut services,” Stenger said. “Secondly, the county’s budget is sound and will remain so. Period.”

The county can balance the budget without raising taxes even as finances tighten in future years by becoming more efficient and doing more with less, including not replacing county employees as they retire or leave, Stenger said. The county has 400 contract employees who rotate out of the county each year and not filling a quarter of those positions is an easy way to trim $6.7 million from the budget.

“I can tell you there is no crisis,” Stenger said. “With respect to what you’re classifying a shortfall, I don’t think it can really be classified as a shortfall. Any shortfall we have would be covered by attrition.”

Stenger outlined several cuts he made to the budget he inherited from Dooley when Stenger took office Jan. 1, 2014, “which was in shambles,” Stenger said.

Dooley’s proposals to close parks to balance the budget were the brainchild of then-county Chief Operating Officer Garry Earls, who is now advising Page.

“Garry Earls proposed selling animals at Lone Elk Park to the highest bidder,” Stenger said. But as 6th District councilman, “I led the fight to stop the sale of our beloved parks, and as county executive, our administration has aggressively looked at ways to cut costs and to improve efficiency.”

The various cuts Stenger has implemented since taking office are saving taxpayers at least $4 million a year, he estimated.

Within months of taking office, Stenger closed the county print shop for an annual savings of $300,000, after discovering that it wasn’t actually used for much printing.

Last year he closed the Lakeside Residential Treatment Center in Maryland Heights, a county-operated facility that provided psychiatric services to troubled youths. He contracted those services to Marygrove, a facility in Florissant funded by Catholic Charities. That move is saving taxpayers more than $2 million a year, he said.

Contracting out food service at the county Justice Center — a move resisted when Stenger proposed it earlier this year by 1st District Councilwoman Hazel Erby, D-University City — saves the county $600,000 annually, he said. Consolidating dental services in the county Department of Public Health is saving “upwards of $1 million” a year, Stenger said.

Since Stenger took office, the county has left 22 positions unfilled to save even more money, with plans to continue with the soft hiring freeze that county Chief of Operations Glenn Powers calls a “hiring slushie.”

Trakas’ takeaway about the operating deficit is that the county is not efficiently run.

“You can’t have it both ways,” Trakas said. “You either have to live within the budget and the revenue that’s generated or you have to generate more revenue or you have to cut more programs.”

But Stenger alleges that at the same time he has tried to downsize county government, the majority of the council, including Trakas and Page, has tried to make it bigger. That includes what Stenger estimates as nearly $1 million in new hires for a new office of legislative research director and suing Stenger to force him to add auditors to the staff of county Auditor Mark Tucker, who Stenger called one of Page’s best friends and unqualified for the job.

“When I refused to grow the size of the county’s auditing staff, Page filed a lawsuit against me and also against the county government he purports to serve,” Stenger said. “His lawsuit could cost county taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars, not to mention adding hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to the county budget.”

It is fine for Page to dislike Stenger, the county executive said, “but attempting to unnecessarily increase the burden on county taxpayers as a means of attacking me cannot be tolerated.”

This summer, Trakas and Page’s alliance fought Stenger to increase county payments to Metro for bus and MetroLink service when Stenger tried to cut it by $5 million.

Page halted changes Stenger proposed for the county retirement plan in September, before saying he now supports the changes in his letter last week. Under the plan, the county’s pension costs for new employees would go down because new hires would take seven years rather than five to vest into the county pension system and would have to contribute to their retirement, which current employees do not have to do. Pension costs are rising as part of the budget, and the proposals are projected to save the county an estimated $30 million over 20 years and up to $300 million over 30 years.