With no historic preservation ordinance in St. Louis County and a wave of developers looking for sites to build, unincorporated South County is losing some historic structures as three separate structures are under threat of being torn down and one is already gone.

The oldest house in Oakville, a stone farmhouse off Fine and Telegraph roads known as the Fine-Eiler House, was torn down by its owner earlier this year — a fact that was revealed when the property came up for zoning for a new McBride Homes subdivision. Two other historic buildings known as the Kassebaum Building or Sessions Building could follow, since QuikTrip proposes tearing them down to construct a gas station at 5040 Lemay Ferry Road. The Concord Farmers Club has been purchased by Lindbergh Schools, although there are currently no plans made for the historic building that stands on the property.

But preservationists see hope in trying to convince the city of Crestwood to move a 200-year-old log cabin listed on the National Register of Historic Places from 10734 Clearwater Drive in Affton to the nonprofit Thomas Sappington House museum at 1015 Sappington Road in Crestwood. The log cabin belonged to Joseph Sappington, Thomas Sappington’s first cousin, and the move would expand the city-owned Sappington House Museum’s houses from one to two — brick from Thomas and log from Joseph. Both are listed on the National Register.

With the wave of potential demolitions on the horizon, the St. Louis County Historic Buildings Commission is now approaching county officials about a historic preservation ordinance. The Missouri Legislature authorized counties to create historic preservation laws in 1990, and preservationists have tried for decades to bring the topic up in St. Louis County with little success. The advisory board offered up a draft ordinance in 2016, but retired county parks historian Esley Hamilton — who has written the book on St. Louis County history — said that then-County Executive Steve Stenger squashed the bill and wouldn’t allow the County Council to consider it.

The county preservationists are experts in their field, but they are not experts in the political navigation needed to get a bill successfully through the council, especially when the county executive at that time strong-armed the bill away from the council’s consideration, Hamilton said. But spurred by the wave of potential demolitions in South County, the historians are working on potential legislation with county Deputy Chief Communications Officer Kat Dockery, an assistant to County Executive Sam Page.

“I think it’s disgraceful. … If we can’t even present the ordinance to the County Council, how can we get them to pass it?” Hamilton said of past efforts. “To have no protection whatsoever when we have buildings coming down every week it seems like — the county has been dragging its feet for 30 years. Soon we’ll have nothing left.”

The most prominent building that could come under the chopping block is the Kassebaum Building built in 1913, more recently known as the Sessions Building for the furniture store that operated there. Hamilton previously led a successful effort to save the Kassebaum Building when it was slated to be taken down for a federally funded widening of Lemay Ferry Road.

“This is another kick in the head for St. Louis County preservation,” Hamilton said. Talking to the Historic Buildings Commission at a May 19 meeting, Hamilton could do nothing but shake his head at the idea that the commission worked to save the buildings from bulldozers to make way for a highway, and now those same buildings could be demolished to make way for a gas station.

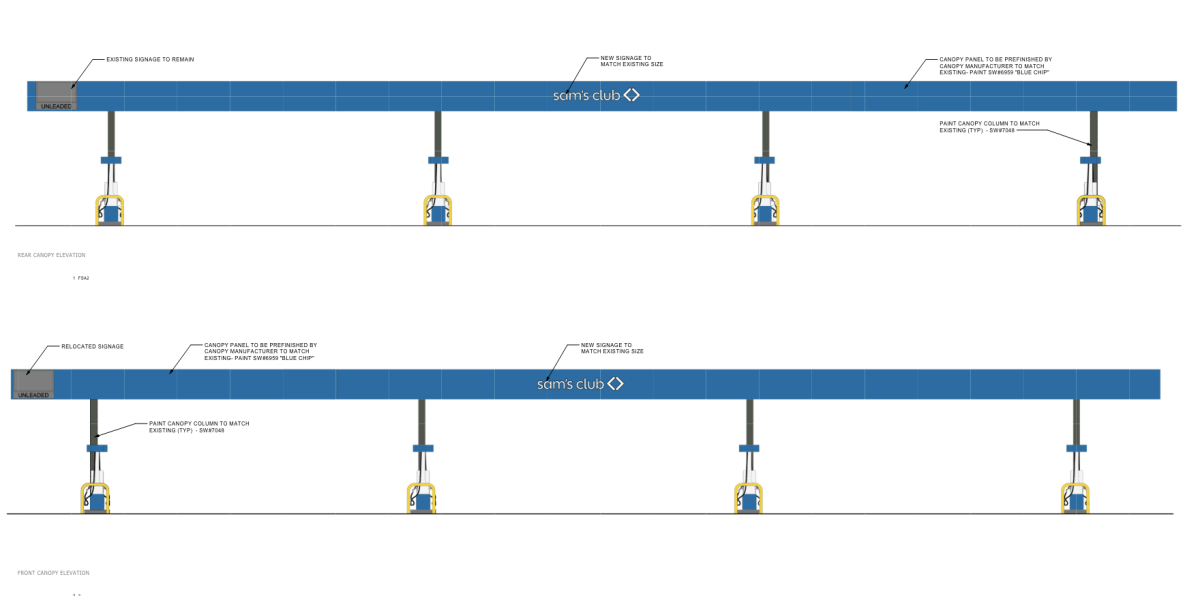

QuikTrip has the property under contract pending zoning, but no zoning plan had been submitted to the county at press time. The County Council would have to approve the project (see Page 26A).

QuikTrip says that the cost to rehab the building is over $3 million, showcasing in photos at a town hall meeting the seemingly sad state of the building. But Hamilton has seen enough developers come and go that he’s skeptical of that figure.

“Usually when the developers show pictures like that, they pile junk in the foreground of the picture and people say, ‘Oh, this looks terrible,’ but that has nothing to do with whether the building is intact or structurally sound,” the historian said.

In the days of August Kassebaum a hundred years ago, there was no St. Louis County executive. Cities were run by sheriffs, and the county was run by three elected officials called judges. The presiding judge — the equivalent of today’s county executive — was Kassebaum.

“And of all the county judges, he was the only one who has any buildings related to him anymore, and his house is just a few doors up from the building where he ran his business,” Hamilton said. “The house was threatened with demolition and we finally were able to find buyers who restored it and turned it into a beauty salon.”

In the past, the Kassebaum Building may not have been as important to St. Louis County history, Hamilton noted. But now it’s one of the few links to the decorative brick facades that used to line streets across the county.

“It’s noteworthy now because all the other buildings like it are being torn down,” Hamilton said. “There used to be buildings like this in the Affton area and in the Lemay area and up north. But they’ve all been torn down.”

The stone Fine-Eiler House in Oakville stood for hundreds of years until its owner — who lives in Michigan — tore it down within the last few months to make way for a McBride Homes subdivision on 26 acres of farmland at Fine and Telegraph roads. The farmhouse was built by Benjamin Fine on property from a Spanish land grant when he married Sara Sappington in the early 1800s. More than 40 years ago, the house was named a countywide landmark by the buildings commission, one of only a few hundred buildings in the county given the honor. To be named, a site has to be historic to the entire county.

But since the farmhouse was never designated for the National Register of Historic Places, it could be torn down at any time by its owner and has frequently appeared on lists of endangered historic places.

The last time a developer tried to build a subdivision on the property in 2014, the county Planning Commission denied the request in part because the developer declined to change its plan to keep the historic farmhouse.

“It was a very good house built of stone, very impressive looking,” said Hamilton.

He sees it as a particular kind of shame when a historic house is torn down and replaced by other houses, probably not built as well, “made out of ticky tacky that probably won’t last 30 years.”

The Concord Farmers Club was the last remaining example of the farmers clubs that used to meet throughout St. Louis County for social gatherings. Original members Adolphus Busch and Eberhard Anheuser are now household names. But the club, which had operated as an event center and was still owned by its original families, closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and sold to Lindbergh Schools in April. The property borders Sperreng Middle School, but officials said they won’t do anything to the land for now. It could eventually be used for ball fields, green space or other facilities needs.

To Hamilton, it’s not much of a compensation that the building was bought by Lindbergh Schools, although he sees nearby Concord Elementary as one of the most beautiful examples of school architecture still operating.

“School districts have torn down their share of historic buildings too,” Hamilton said.