By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

glorialloyd@callnewspapers.com

Voters in St. Louis County could be the tipping point in a statewide vote next week to decide once and for all whether Missouri will be a “right-to-work” state or not.

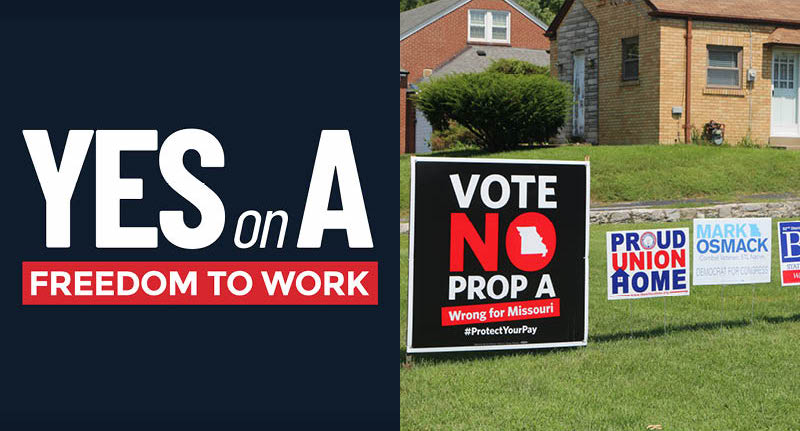

Voters will decide on the matter Tuesday, Aug. 7, when they will consider Proposition A, a referendum to either ratify or strike down the right-to-work law passed by the Missouri Legislature last year, which has not yet gone into effect pending the referendum.

A “yes” vote enacts the law. A “no” vote rejects right-to-work and keeps unions’ ability to charge workers mandatory fees.

Right-to-work legislation bans labor unions from making membership fees mandatory for all workers in a “closed shop,” or unionized business. Supporters of the legislation say that striking the mandatory fees would lead to job growth and make Missouri more attractive to businesses. But organized labor groups say the fees are used to negotiate for better wages and benefits such as health care and pensions.

Former Gov. Eric Greitens was elected in 2016 on the central platform of making Missouri a “right-to-work” state, which he said would create more jobs and make the state more economically competitive with other states. The Legislature passed right-to-work soon after Greitens was inaugurated, in one of the few times Greitens actually came to agreement with the GOP legislative majority before he resigned from office this year.

But Greitens’ signature legislation never went into effect because unions immediately objected and gathered more than 300,000 signatures against the law, enough to place a referendum on a statewide ballot.

A few months ago, Republicans moved the law from the November ballot to the primary election. Jumpstarting the state’s economy couldn’t wait a few more months, they said. Naysayers said Republicans wanted to move the statewide vote so that it didn’t affect the outcome of the U.S. Senate race that is widely expected to position Republican Attorney General Josh Hawley against incumbent U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Kirkwood.

Business-oriented groups said the vote on right to work couldn’t wait a few more months.

“Every day that goes by that our economic developers in this state cannot advertise Missouri as a right-to-work state prevents us from being able to take advantage of the right-to-work benefits,” said Ray McCarty with Associated Industries of Missouri, a business-lobbying group.

If Missourians keep right-to-work, the move would hardly be out of step with trends nationwide: 28 states have right-to-work laws.

Every state bordering Illinois has had right-to-work legislation go into effect in recent years except Missouri. When Indiana passed right to work in 2012, it ushered in a trend among Midwestern states. Wisconsin, Michigan and Kentucky have all approved right-to-work in the years since. But voters in Ohio took the opposite tactic, overturning a right-to-work law in 2011.

Opponents of right-to-work call it “right to work for less” and argue that states with the law have lower average wages than states without. But supporters say that statistic is misleading because it counts large non-right-to-work states like California and New York, which have a higher cost of living and therefore higher wages than what you’d see in Missouri anyway.

National unions have poured millions of dollars into the Missouri campaign, and AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka joined County Executive Steve Stenger at a kickoff rally in June to denounce right-to-work as bad for Missouri.

Unions fear that right-to-work could lower union membership, damaging their ability to collectively bargain for their workers.

Union membership in Missouri rose to 9.9 percent of the work force, compared to 9.4 percent in 2009. In contrast, union membership in Indiana fell 12.5 percent this year to 8.9 percent, down from 10.4 percent in 2016.

“Right to work ends forced unionism and lets workers decide whether joining a union best serves their interests,” the free-market think tank Show Me Institute said in its 2018 Blueprint.

Whether or not the policy helps the state economically, principles demand that workers be given the freedom to decide whether to give their money to unions, the think tank said.

Right to work would hurt small businesses because on average, states that are right to work have 50 percent lower overall family income than states that are “closed shop” like Missouri, Sen. Scott Sifton, D-Affton, said at a July 11 joint luncheon of the Affton and Lemay chambers of commerce.

“And that money gets spent at your businesses, and if Prop A passes, that money’s not going to be spent at your business anymore because it’s no longer going to be coming into folks’ paychecks,” Sifton said. “I’ll be voting no on Prop A.”

Nationally and in Missouri, the Chamber of Commerce is in favor of right to work, noting that growth in states with the policy was 17.4 percent between 2001 and 2013, which more than doubles the 8.2- percent growth of non-right-to-work states in those years.

Unemployment is also half a percent lower in those states on average, the chamber said.

But on the flip side, salaries are 3.1 percent lower, or $1,558 less a year, in states with right-to-work compared to non-right-to-work states, according to data from the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal-leaning think tank with ties to labor.

The last time right-to-work legislation came up for a vote in Missouri was 1978, when Stenger was six years old. His father piled the family in a Pinto and took them out on many weekends campaigning against right-to-work.

Stenger said approving right-to-work will harm workers like his father, who was a union lineman for the telephone company and “came home every night with his work all over him. He dug ditches, he dug trenches, he dug everything that you would do as one of the hardest-working people I’ve ever met in my life.”

When Stenger was 10, they went on a picket line, which showed him the power of unions to bring home better working conditions, he said.

“And I can tell you what he told me then and what he would be telling me now if he were alive – if our union brothers and sisters’ wages go down, if their wages are lost, they really set an important standard for everyone in this room and everyone in our community. We just can’t have that happen,” Stenger said. “And when you lose the right to collectively bargain and those rights are diminished, it hurts everyone.”

The issue is one of the few that Stenger and his opponent in his re-election bid, Mark Mantovani, agree on. Mantovani said he plans to vote “no” on the measure.