By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

glorialloyd@callnewspapers.com

The backers of a city-county merger for St. Louis County and city are saying that the plan will save taxpayers across the region $55 million a year from the start and up to $1 billion annually a decade after the start of the new megacity.

Those are the numbers nonprofit organization Better Together released last week, which don’t take into account any tax increases on municipal residents to make up for their former city’s sales taxes being redirected to the “metro city.” The organization also issued the caveat that the numbers were based on its own “pro forma” budget numbers, not the budget that leaders of the new city, like County Executive Steve Stenger, would actually propose.

With those parameters in mind, the organization says that starting in the first official budget year of 2023, the merger would save taxpayers of the region $55 million annually, which could grow to $1 billion annually by 2032.

That would capture much of the overspending that Better Together found in what St. Louisans pay for local government services in one of its five studies leading up to its proposal for a merger.

The studies found the region overpays $750 million for local government, although that includes fire districts, which are not going to be touched by the plan.

The new metro city would have a $2 billion budget under the estimates, which is less than the $2.5 billion the region spent on local government in 2017. The current spending is $790 million for the city of St. Louis, $730 million for the county municipalities, $700 million for St. Louis County and $200 million on fire protection districts.

Better Together says the metro city’s savings will recapture much of that overspending, even with fire districts continuing to spend $300 million a year and county cities, now called municipal districts, continuing to spend an estimated $350 million a year under the plan.

The cost-saving aspect of the plan was brought up by Stenger at the campaign kickoff Jan. 28.

“Imagine paying for police and other municipal services through a taxing system that levies an overall lower burden versus the current system of ever-multiplying sales tax districts on top of ever-increasing property taxes,” Stenger said.

Although Better Together’s numbers seem to some to be too good to be true, the organization says its budgeting is “conservative.” The $55 million comes through an estimate of 1-percent cost savings over inflation.

Both Stenger and St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson have promised that no city or county jobs would be lost under the merger plan, and pensions would be protected. Instead, Stenger and Better Together envision shrinking the number of city- and county-paid employees through attrition, especially in the city workforce, which is slated to see hundreds of retirees each year.

Better Together came up with its savings estimates by combining “reductions in expenditures” along with surpluses of revenues over expenses, according to the executive summary attached to the pro forma budget. Over the first decade of the new city, Better Together says the metro city could reduce overall regional expenditures by as much as $3.2 billion compared to the current trend of spending in the region, which is increasing as cities across St. Louis County go for more and more tax increases. Over that same decade, the metro city would have surpluses of $1.7 billion, generated from the region’s sales taxes which currently go to cities in the county.

By 2025, the metro city is expected to rake in $1 billion in sales taxes, Better Together said. By 2032, the organization says the metro city could have a budget surplus of $342 million if additional efficiencies and cost savings through economies of scale are realized such as employee attrition, service consolidation and implementation of new technology.

The savings will happen even with the phase-out of the city earnings tax, payroll tax and a promised reduction in county property taxes in St. Louis city and in unincorporated areas of St. Louis County like Oakville.

Earnings tax goes away

Better Together and the proposed statewide campaign are financially backed by billionaire megadonor Rex Sinquefield, who is a noted opponent of the earnings tax in St. Louis city. One of the keystones of the plan is that St. Louis city would pay off its debt and pension obligations through the phaseout of the earnings tax over the first decade of the megacity.

The new metro city would take over most city services of the former St. Louis County and the former St. Louis city, along with all the other county cities like Sunset Hills and Crestwood. To pay for that, it would take the sales taxes that now fund St. Louis County and the county’s cities.

The earnings tax, which is levied on everyone who lives or works in the city, even for a day like out-of-town professional athletes, currently funds a third of St. Louis city services. With St. Louis city freed from using the earnings tax for paying for those services under the metro city, the earnings tax could be redirected to pay off the city’s $1 billion in bond debt and outstanding pension obligations. The St. Louis Fire Department would become the St. Louis Fire Protection District under the plan, which would have its own taxing authority over the St. Louis Municipal District just like any other fire district in the county. But for the first year of its operation, the metro city would fund it.

St. Louis County employees forced to pay the earnings tax will receive a tax credit to make up the difference. The plan does not call for anyone outside the current lines of St. Louis city to pay the tax, such as current St. Louis County residents.

Dispute over municipal money

Better Together’s pro forma budget states that former county cities will still spend around $350 million annually on parks, trash and other services, and “municipal districts will have excess revenues over expenditures following reorganization” since they will no longer have to provide basic city services.

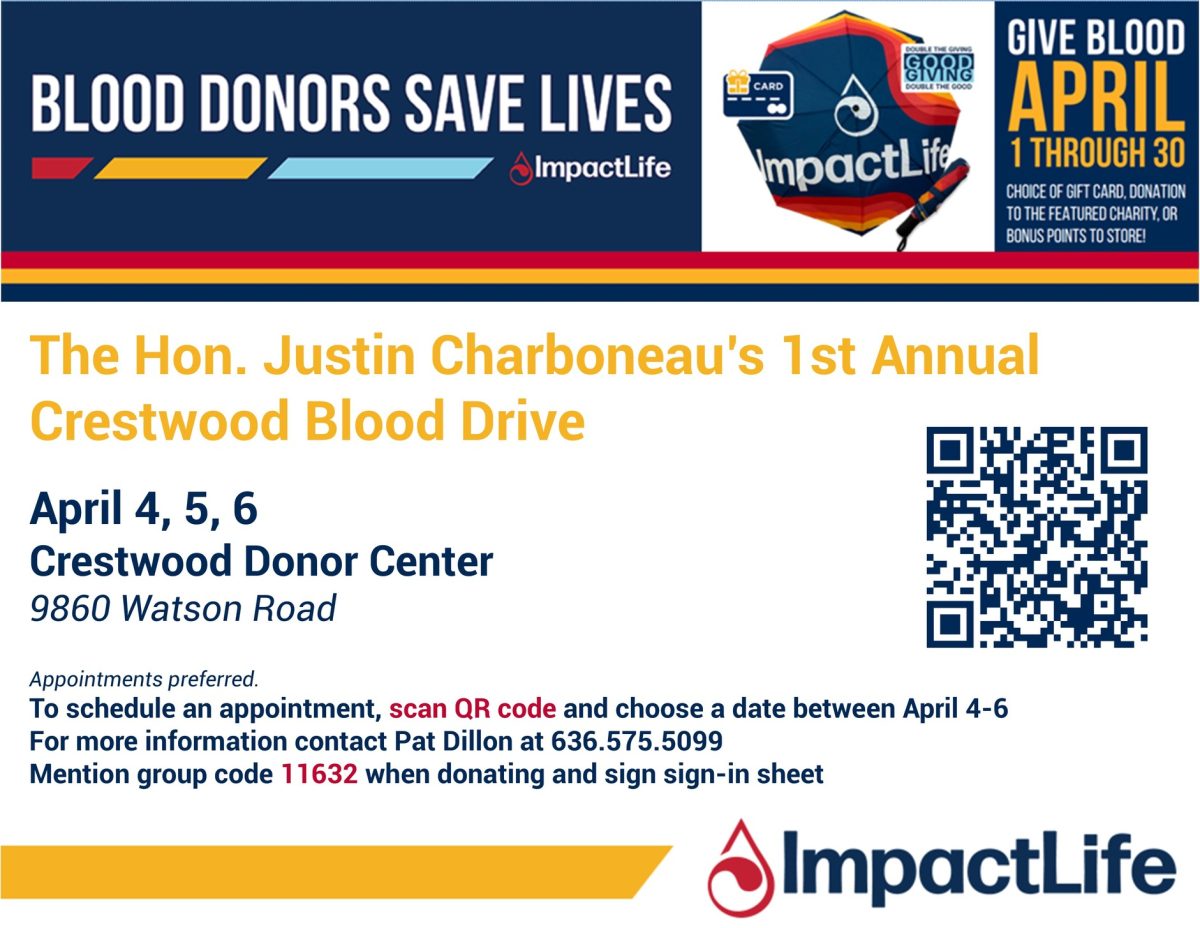

But some of the cities involved are disputing that analysis. Crestwood city officials sent a fiscal note to state Auditor Nicole Galloway saying that even if its Police Department, courts and local zoning were abandoned, the city would be underwater under the merger plan. It would lose $6 million in sales taxes, but it wouldn’t need all of that to operate because of no longer providing a Police Department. Even with hiking property taxes on city residents to the maximum allowed by law, the city would still be $1 million in the red because it would need money to operate.