Last week, multiple mass vaccination events in rural areas neared the end of the day with hundreds of doses still on hand — prompting health departments to take to social media and encourage anyone to come for fear doses would be wasted.

“We have ample vaccine still available that needs to be administered today,” the Putnam County Health Department wrote on its Facebook page around 4 p.m. on Saturday. “Anyone 18 and older that would like a vaccine may come and get in line.”

In Putnam County, on the Iowa border, out of 2,340 Pfizer vaccine doses received there were 143 wasted and 1,488 redistributed for use later in the week.

Days before, similar situations played out at mass vaccination events across the state. In Leopold, even after opening its event to those without an appointment, only 648 doses out of the 1,950 allocated were administered — about one-third. The remaining doses were redistributed, state officials said.

The issue isn’t new — some of the state’s first mass vaccination events ended the day with hundreds of extra doses. But recently, the frustration has boiled over, as residents’ names languish on waitlists as they grow increasingly frantic about when it will be their turn.

The frustration is especially acute in the state’s urban metros, prompting experts and lawmakers to question the state’s distribution model and renew calls for change to ensure equitable distribution around the state.

“It is beyond disappointing,” said state Sen. Jill Schupp, D-Creve Coeur. “These are doses that make a difference in a person’s life and health. So we can’t afford to be sending them to places that don’t have the numbers of people that actually need the doses.”

Gov. Mike Parson on Monday signaled change was on the horizon, announcing adjustments to Missouri’s vaccine distribution model.

Citing rising vaccination rates and an anticipated increase in supply due to the arrival of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine this week, Parson announced planning is underway to transition some mass vaccination teams to the St. Louis and Kansas City regions.

Of the 50,000 Johnson & Johnson doses expected to arrive in Missouri this week, 5,000 will be distributed toward targeted sites in St. Louis and Kansas City, 10,000 toward mass vaccination events and 35,000 toward community providers who were not allocated Moderna or Pfizer vaccine this week, according to Monday’s news release.

In addition, going forward 15 percent of the state’s weekly supply will go toward “vaccine desert mitigation.” An analysis of Jan. 18 data by a consulting firm hired by the state found an expanding portion of St. Louis and Kansas City were considered “vaccine deserts,” or areas with limited-to-no access to the COVID-19 vaccine.

‘It’s very upsetting’

Rep. Sarah Unsicker, D-Shrewsbury, said outrage among her constituents in her St. Louis County district has been building as they struggle to find nearby appointments and are forced to drive hours to more rural areas in search of a vaccine.

Democratic Rep. Patty Lewis, D-Kansas City, said she has been inundated with emails from Jackson County residents, many who are over 70 years old or have pre-existing conditions, and have signed up on every list and are still waiting their turn.

“And then I see, you know, double digits in rural (counties),” Lewis said, in reference to higher rates of rural residents with at least their first dose. “It’s very upsetting.”

Lewis said she would like to see facilities closer to the state’s population centers, like Arrowhead Stadium which is home to the Kansas City Chiefs, be used as mass vaccination sites.

“Quite frankly, I’m just at a loss for words,” Lewis said.

The frustration has spawned the creation of Facebook groups that have created an underground network of helpers who post tips on where to find available appointments, exchange questions and share success stories.

One Facebook group targeted toward the St. Louis region has over 22,000 members.

Unsicker said some of the frustration stems from city residents who aren’t as used to driving to access healthcare, which is often some rural residents only option in the face of hospital closures.

“I don’t think that should be happening anywhere,” Unsicker said.

In a letter sent earlier this month, Unsicker requested Randall Williams, the director of Missouri’s state health department, “immediately rectify this situation” by distributing sufficient doses to bring St. Louis city and county on par with the statewide average in terms of the percent of residents vaccinated.

On Friday, Unsicker sent a records request to the Department of Health and Senior Services requesting data related to the number of vaccines sent and administered at the event in Leopold, as well as where doses were redistributed and how many went unused.

Unsicker said Monday she has not yet received responses to either letter.

In response to questions about unused doses from last week’s events, Mike O’Connell, a spokesman for the Department of Public Safety, said the Missouri National Guard is working to pull that data. In a statement last week, O’Connell said the state is working with local providers “to ensure the amount of vaccine allocated more closely matches the need within the area for scheduled mass events.”

Distributions of vaccine

This week, mass vaccination events with the support of the Missouri National Guard will be occurring in North Kansas City and St. Louis. But for some residents, the unused doses at mass vaccination events last week combined with events consistently being held hours outside of city centers, fueled their suspicions that urban areas were purposefully being shorted their fair share of vaccine.

U.S. Rep. Cori Bush said she requested Missouri’s plan for ensuring equity in vaccine distribution weeks ago — and is still waiting on it.

“We need answers,” Bush wrote on Twitter Monday. “Now.”

Gov. Mike Parson has repeatedly pushed back on assertions of an urban versus rural divide, noting that doses are being allocated proportionally based on each of the nine Highway Patrol regions’ populations.

“Due to health care infrastructure, distribution methods may vary from one region to the next, but there is no division between rural and urban Missouri,” Parson said in a statement Monday. “Individuals willing to do their homework will learn that each region, whether it be urban or rural, is receiving a percentage of our state’s total vaccine allocation that matches their region’s population size.”

But whether doses are being proportionally allocated within each region is unclear.

Data requested from Schupp’s office showed that in the first two months of Missouri’s vaccine distribution, Cape Girardeau County received enough vaccine to cover over half of its population, while some other counties — both rural and urban — didn’t have enough doses for even 5 percent of their residents.

But the state has said those numbers don’t show the full picture and leave out hundreds of redistributions across county lines that would skew those totals.

Meanwhile, counties still vary widely on the percentage of their residents with at least the first dose — with the top counties reaching over 20 percent, while more than two dozen have less than half that at under 10 percent.

Chris Prener, an assistant professor of sociology at Saint Louis University who has been closely tracking and compiling data on the virus’ spread and vaccinations in Missouri, said it’s difficult to pinpoint what exactly may be leading to disparities in vaccination rates between counties.

“It’s not clear with the public data if that’s because there are issues with deliveries, so some areas are getting more deliveries than others. Or if it’s administration issues, so some areas are simply getting vaccines to people more efficiently than others. Or if there’s some other reason,” Prener said. “It’s very unclear to me.”

But without a change, Prener said it will continue to be an inefficient and inequitable system.

“We shouldn’t rely on people having the ability to literally drop everything in their lives and drive for a few hours to get a vaccine,” Prener said. “That’s just going to exacerbate racial differences. It’s going to exacerbate class differences.”

Calls for a new distribution model

As a solution, some have called for the distribution model to change.

Public health officials previously had reservations about the state’s use of Highway Patrol regions and mass vaccination events when plans were getting off the ground. In January, members of the Missouri’s Advisory Committee on Equitable COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution said allocating a large share of the state’s limited doses toward the events would make distribution less equitable and wondered how events would be tailored by region to account for population differences.

Schupp has suggested congressional districts be used to more accurately reflect equal populations for each region. And Unsicker said the state should be allocating doses proportionally based on counties or regions smaller than the Highway Patrol districts.

Prener said with the vaccine still restricted to only certain tiers, he wouldn’t expect equal distributions between counties or congressional districts.

“Right now to me, it’s not about changing the unit. It’s about saying, ‘Here are the estimated number of people in that unit that we think are vaccine eligible,’” Prener said.

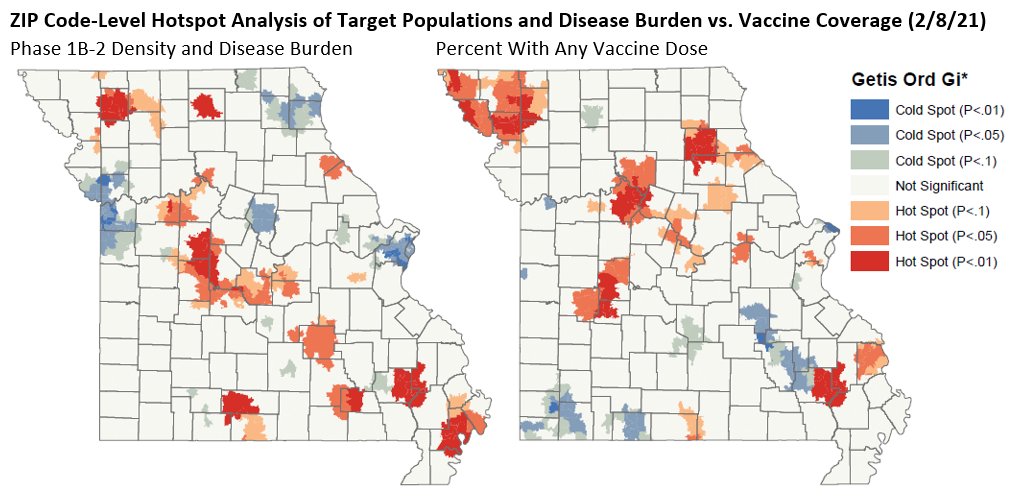

According to a Feb. 8 analysis by the Missouri Hospital Association, areas of the state where residents received at least one dose had a positive association with areas where concentrations of high-risk residents combined with historical disease burden.

“This association reveals a degree of success in the state’s targeted distribution efforts to date,” the association wrote in its Feb. 9 newsletter.

Hospital systems in the Kansas City and St. Louis areas are within the regions receiving the largest share of doses allocated toward the state’s “high throughput” locations.

But the mass vaccination events that have been occurring for the last five weeks may be a sticking point that has contributed to higher vaccination rates in more rural areas. In weeks past, the state has been sending roughly equal amounts to each mass vaccination event — and for the month of March anticipates sending higher totals to the Kansas City and St. Louis regions, according to estimates shared on a call with vaccinators last week.

But because of population differences, those doses don’t have the same impact.

“Two thousand doses at an event in Sedalia, Missouri, are gonna go at a very different pace than 2,000 doses in St. Louis,” Prener said.

Schupp has called for the state to revise its formula or add more events to more heavily populated areas, and Unsicker said the state should ensure demand meets the number of doses being sent. Williams has said mass vaccination events were targeted toward rural areas because they often lack hospitals and healthcare infrastructure.

Larry Jones, the executive director of the Missouri Center for Public Health Excellence, said that in smaller counties, like Putnam and Bollinger, where there were unused doses at the end of mass vaccination events, it may make more sense to do multiple smaller clinics of about 500 doses to ensure all the vaccine will be used at one time.

But those counties were simply trying to do the best they could, Jones said.

“It’s better for it to go into an 18, 20-year-old than it is to not get used, period. Because eventually we’re going to reach those age groups,” Jones said. “Now, that doesn’t make the 80-year-old person in St. Louis or Kansas City feel any better who hasn’t been able to get their vaccine.”

Joetta Hunt, the administrator for the Putnam County Health Department, said in a news release Monday that the wasted doses were in part due to scheduling issues through Vaccine Navigator, the state’s centralized registration system, as well as no shows, dislodged needles and extra vaccine drawn that passed the six hour time limit it needed to be used by.

“We made every effort we could to utilize this extra vaccine within the appropriate timeline,” Hunt said. “We have learned much from this experience and know where we can improve and we will do better next time.”

As the state’s supply increases, through the introduction of a third vaccine with Johnson & Johnson and doses being shipped directly to retail pharmacies like Walmart, Jones said he anticipates the methodology for distribution will change.

Mass vaccination events will likely still be useful tools for larger cities — especially when the state opens the tiers up to all residents. What will be needed in both rural and urban areas is more partnerships with trusted community centers, better communication for those without internet access and improved transportation and times for appointments, like during nights and weekends, Jones said.

For those frustrated with the rollout at both a local and state level, Jones encouraged residents to be part of the solution.

“If you see something that you think would work in your community, say so,” Jones said. “Let the state know. Let the local public health department know. Let your city council member or county commissioner or whomever know, because there’s nobody that’s wanting to keep vaccine away from people.”

This article is from the Missouri Independent.