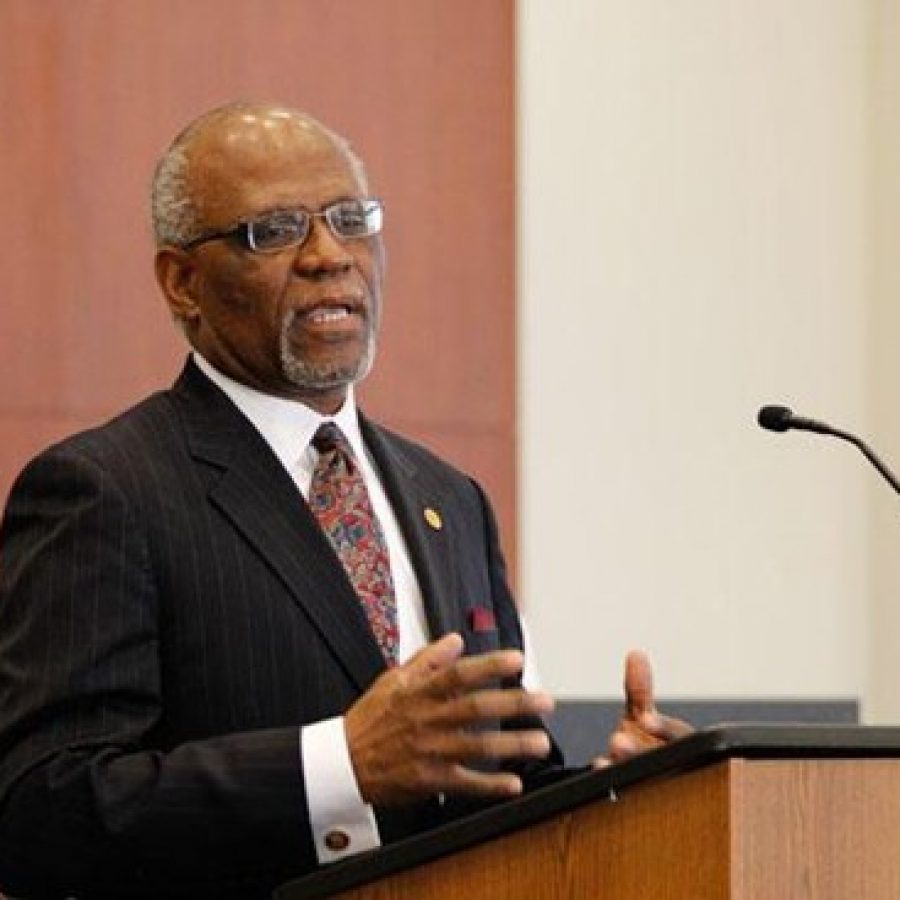

In what can only be called a sea change, former County Executive Charlie Dooley’s name was never spoken at the first major St. Louis County government event in 11 years that didn’t include him — last week’s inauguration ceremony for his successor, Steve Stenger.

Stenger resoundingly defeated Dooley in the Democratic primary for the county’s top job last August, but the legacy the outgoing county executive leaves on St. Louis County after 20 years in county government is less clear-cut than how it all ended.

Whatever county government looks like after the Dooley era, it will certainly have fewer tailored suits and fewer times when the county executive calls everything about the county “simply outstanding,” as Dooley so commonly did even up to last summer, before Ferguson.

And, of course, no more glimpses of “Combat Charlie” in action: Stenger once promised the Call that he would never confront county residents at council meetings the same way Dooley regularly did as both 1st District councilman and county executive.

And while Dooley has not yet announced his next move, he has said that after 35 years as an elected official in St. Louis County, he is retiring from public life. As if to emphasize that in the most resounding way possible in the social-media era, Dooley deleted his two Twitter accounts even before he left office.

If Dooley had been re-elected, he would have celebrated his 20th anniversary in county government at the Jan. 1 inauguration ceremony. Instead, the day of Stenger’s inauguration was the same day Dooley, 67, became a civilian, rather than an elected official, for the first time since he was originally elected to the Northwoods Board of Aldermen in 1978.

Dooley, a Vietnam veteran and union worker at Boeing with a high school education, eventually served as his city’s mayor, and was later elected to the County Council and then, after former County Executive George R. “Buzz” Westfall’s death in office in 2003, he was appointed and then elected county executive.

Even in times of strife, when he acknowledged the racial divide that the whole world came to know post-Ferguson, Dooley — the first black county executive, and before that, the first black county councilman — could also be the county’s most outspoken cheerleader, noting that the county and the country gave him opportunities he never thought he would have. He never missed an opportunity to say, “Anything is possible in America. It’s a great country.”

Ever the optimist even as he was under fire for a series of scandals in recent years, Dooley maintained that even in an economic downturn, the county was “second to none to nobody,” the economic engine of the state.

He came up with countless ways to phrase it, but the message from “AAA Charlie” was always the same: St. Louis County is the best Missouri has to offer.

“Let’s not jump off the boat. The boat is still floating,” Dooley said last year. “It’s the best boat in this state.”

From the perspective of former Chief Operating Officer Garry Earls, one of Dooley’s most significant accomplishments is setting the county up with infrastructure to operate for decades. The wish list of construction projects the county outlined in hopes of receiving federal stimulus funding is entirely finished or under construction, which Earls called a rare and remarkable accomplishment.

Dooley’s keystone project was the $550 million Interstate 64 renovation, which was finished faster because Dooley pushed for all the lanes to be closed.

“(Charlie Dooley) made this happen,” Earls said.

Other major projects in the county, both public and private, that are the direct result of Dooley’s leadership include the $380 million River City Casino and the $14 million aquatic center in Lemay, the $130 million new Family Justice Center set to open this year and courthouse renovations to be finished next year, new police precincts, including the new South County Precinct set to open next month, and the new $10 million police crime laboratory, Earls said.

“This list could get really long,” he told the Call.

Other projects Dooley oversaw include the development of the North Park corporate park that houses Express Scripts and 6,000 jobs in north county, the redevelopment of the North County Recreation Center, the new health department headquarters in Berkeley, the new animal shelter in Olivette and the new emergency communications center in west county, along with a new communications system for first responders in three counties.

During his last days in office, Dooley said he views the establishment of the county’s trash districts as perhaps his biggest accomplishment.

But while the events of the past few years — Dooley’s threat to close half the county parks, the $3.5 million embezzlement by a health department administrator, the various FBI investigations that Dooley maintained were not FBI investigations — propelled Stenger to the county executive’s office, it might have been the trash districts that proved to be Dooley’s undoing, since they were so unpopular in south county that they formed the basis for Stenger’s initial 2008 run for the council.

“What he’s claiming to have as his signature accomplishment has been the subject of a multi-million dollar lawsuit, so I don’t know — that’s an interesting signature accomplishment,” Stenger told the Call before he took office as county executive.

A $6 million judgment against the county over the trash districts is still pending, gathering interest daily, and the county will most likely have to pay an unknown amount of restitution to trash haulers who were not notified when the county established eight trash districts and took bids for mandated service.

Some south county trash cans set out every week still sport “Dump Dooley” bumper stickers, but to the end, Dooley and Earls defended the trash districts for saving residents money and promoting recycling.

During Dooley’s first county-executive campaign in 2004, he promised at a forum in south county, “But let me tell you this, I will never do anything to infringe upon those rights. If south county wants something or they don’t want something, I’m going to listen to you. I’m going to listen to what you want.”

The trash districts led many south county residents to believe otherwise, however.

Although during his last days in office Dooley blamed this on race, his alienation from south county voters came long before a long series of later decisions that only served to cement that divide — the proposed Fred Weber trash-transfer station, the National Church Residences Telegraph Road senior apartment complex so many Oakville residents objected to and the relocation of the Tesson Ferry Library.

Stenger once told the Call during the fight over parks that Dooley was “essentially being attacked by reality,” making proposals that “99.999 percent of the people in the county and probably on the planet” would oppose. While no one knows what weighed on voters’ minds the most, it added up over time, and on Aug. 5, voters chose Stenger over Dooley in a landslide in the Democratic primary.

Tellingly, Dooley campaigned in every area of the county that day — except south county.