Since the coronavirus struck Missouri in early March, university researchers across the state have postponed their projects. Some have found a new focus: the COVID-19 pandemic itself.

Some researchers began new projects even as their labs and campuses closed. Some left behind their usual specialties. Some started looking at COVID-19 because it was their only chance to do research. And some began studying the virus because there was a need for it.

Public health messaging

An interdisciplinary group at the University of Missouri-St. Louis is researching public health messaging about COVID-19 in under-resourced St. Louis neighborhoods.

Their goal is to study how to better communicate public health information to these communities. The researchers will look at the intersection of issues like poverty, disability, location, English proficiency and broadband access, as well as the negative health outcomes of COVID-19.

“I think it’ll also tell us something about disparities and ways in which we can use health information within other situations outside of COVID-19 in order to help to reduce some of those disparities,” said Stephanie Van Stee, assistant professor in the Department of Communication and Media at UMSL and one of the researchers on the project.

The researchers are trying to answer a number of questions: Where are people in marginalized communities getting their information about COVID-19? How effective is public messaging in changing people’s attitudes? What is the content of these messages? Does it get them to engage in healthy behaviors and help them find testing centers?

They also hope to find better ways for public health departments and policymakers to communicate in times of crisis and periods of recovery.

The researchers come from sociology, philosophy, political science, psychological sciences, communication and media, the National Security and Community Policy Collaborative and the Community Innovation and Action Center.

“So, it’s really quite the diverse group in terms of experience and expertise. We’re trying to cross several disciplines in our approach to this,” Van Stee said.

In May, the group received $1,000 in funding from CONVERGE, a National Science Foundation-funded initiative based out of the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

“Our plan is to use the $1,000 grant that we received to work on some pilot projects, and we hope to use that initial data in that initial work in the community to get larger external grants to continue our research in this area,” Van Stee said. “The most important goal is to benefit under-resourced areas in our community.”

On June 17, the group completed a paper for CONVERGE. Now, they are planning one or more pilot projects to gather initial data and information that will help them better understand what’s going on in their community.

Analyzing COVID-19 data

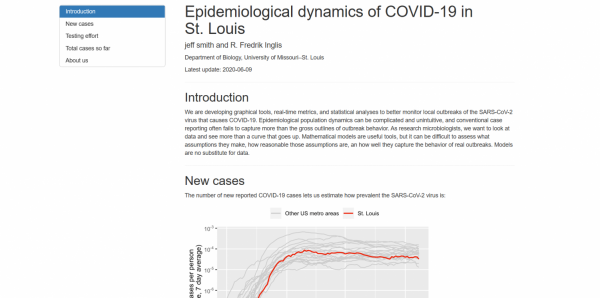

Fredrik Inglis and jeff smith (sic) usually study the evolution of interactions among bacteria and amoebae.

But they lost the ability to work in their lab at the University of Missouri-St. Louis when the University of Missouri System campuses closed in mid-March.

So Inglis and smith decided to take on a new project.

“When the pandemic happened, we found ourselves in an adjacent field. We were already interested in the ecology and evolution of infectious disease, so we were just trying to find some way to contribute,” said smith, who is an independent researcher and data scientist in St. Louis, in an email.

The researchers are analyzing data on COVID-19 to understand how the virus is spreading in the St. Louis area. They are tracking what areas have been hit the hardest and are providing more context to testing data, among other things.

In the city, wealth and poverty are separated by mere blocks, so the researchers are looking at whether these socioeconomic factors influence the spread of COVID-19. Wealthier areas tend to have better access to health care, said Inglis, who is an assistant professor in the biology department at UMSL.

Inglis and smith are using data from the Johns Hopkins University Center for Science and Scientific Engineering, which collects data on reported cases around the world. They are also using data from the COVID Tracking Project, which gathers numbers on tests, confirmed cases, hospitalizations and patient outcomes from every U.S. state and territory.

Inglis said one of the team’s big issues is just getting good data.

“It’s even hard for us to access county-level data, which you could imagine should be freely available to research scientists,” he said.

The researchers are publishing their preliminary findings onto a website and plan to submit to a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

And where do they see their research going?

“Hopefully come at it from a different angle, and we will have something interesting to say … (to) open lots of new doors and avenues of curiosity,” Inglis said.

Tracking COVID-19 in wastewater

Marc Johnson, professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Missouri-Columbia, primarily studies HIV. But when the pandemic hit, he realized his skills could also be used for other viruses.

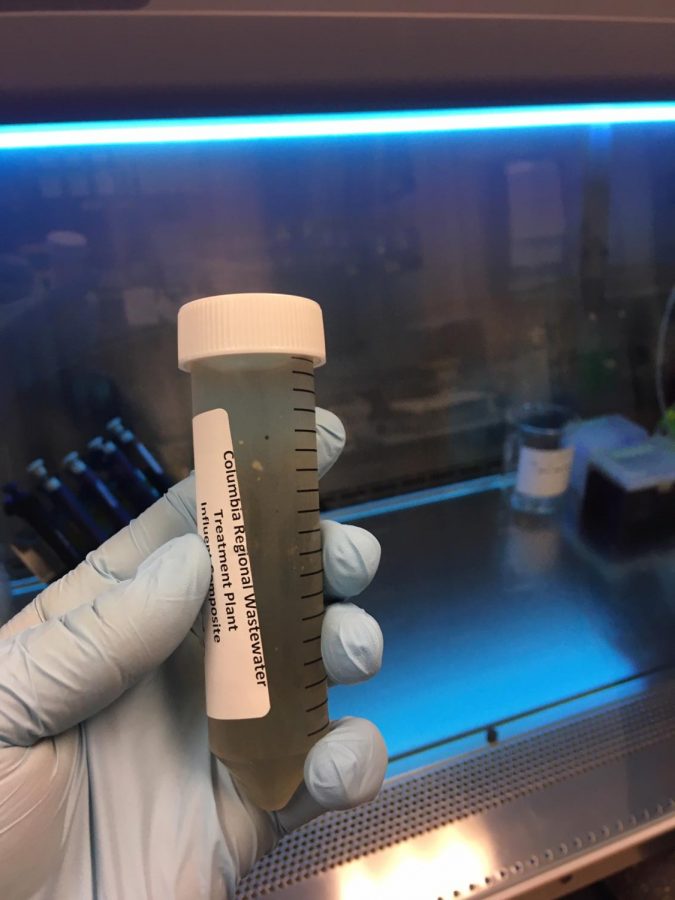

Now, Johnson is working with Mizzou biologists, hydrologists, pathologists and engineers to detect and quantify the amount of COVID-19 particles in wastewater. The research team is planning to study samples from places like municipal water treatment plants, meat-processing plants and prisons across the state.

For Johnson, the project began when the state of Missouri recruited him to help process COVID-19 particles found in wastewater.

When a person is infected with COVID-19, they have millions of dead viral particles in their feces, Johnson said. This means they are depositing pieces of COVID-19 into the water supply.

Missouri collects samples of wastewater, but it doesn’t have the laboratory capacity to measure the amount of COVID-19 particles, Johnson said.

At first, Johnson was skeptical that he could help. But he realized the state’s methods were similar to what his own lab usually does.

The researchers plan to take samples from the water supplies of about 80 municipalities around the state. This could reveal spikes in COVID-19 infection rates without performing tests on individual people.

Theoretically, it’s one test for the entire community, Johnson said.

Based on their findings, the researchers will develop ways to reduce community exposure to COVID-19.

They will also map the spatial distribution of COVID-19 particles in watersheds.

Mapping to show the spread of COVID-19 is one way researchers can share their work with the general public, said Chung-Ho Lin, associate research professor at MU’s Center for Agroforestry and a member of the project.

The research project is still in its early stages. The researchers are collecting baseline samples because every water supply will be different.

“How much water there is per gram of feces is going to vary from watershed to watershed,” Johnson said.

Lin said he hopes this research project will be a tool for regulatory agencies, health agencies and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to validate or improve their own models.

Missouri officials are also interested in using the research to prioritize where testing happens, especially in vulnerable communities, Lin said.

“A lot of low-income, low socioeconomic status communities (are) concerned about medical expenses. So, a lot of (people), even though they have symptoms, they won’t go to get a test,” he said.

The researchers receive wastewater samples in vials to test. Photo courtesy of Marc Johnson.

Comparing pandemics

When COVID-19 reached the U.S., Lisa Sattenspiel and Carolyn Orbann saw an opportunity.

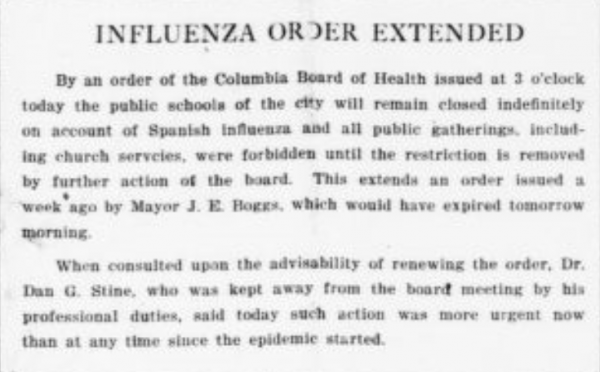

Since fall 2018, Orbann, an associate teaching professor in the Department of Health Sciences at MU, has been working alongside undergraduate health sciences students to collect data on the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic in Missouri. They’ve used death records, diary entries, letters and newspapers to learn more about how the flu affected Missourians.

Because Orbann already had the data on flu deaths, Sattenspiel, who is a professor and chair of the Department of Anthropology at Mizzou, suggested there could be parallels between the past pandemic and the current one.

“I started to kind of think about, well, I wonder if we’re going to see things that are similar in COVID as it happened in the pandemic in 1918,” Orbann said.

Now, the original project has expanded to include researchers from many different backgrounds: engineering, statistics, anthropology, biology and immunology. Their research is focused on studying how humans behave during a pandemic, then and now.

A multidisciplinary group of flu researchers had been collaborating on other flu-related projects since fall 2019. Orbann joined the group just before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. The group discussed how the data Orbann had already collected might contribute to a project that addressed the current pandemic.

“So, I think it’s important not to draw really, really close parallels, but to draw kind of bigger picture parallels between the two pandemics,” Orbann said.

For example, in the letters Orbann has read, the writers speak of the challenge of not having social interactions.

The research team plans to look at a wide array of information at the county level from 1918-19 and 2020, including demographic data, death rates, average socioeconomic status and the availability of medical resources.

The researchers are looking at whether these factors can help people today predict what the impact of infectious diseases might be.

The goal is to “maybe get a little bit closer to understanding and being able to really plan for potential problems in the future,” said Sattenspiel, who is the project’s principal researcher.

To gather information for COVID-19, the group needed to get more funding. On May 12, they were granted about $146,000 through the National Science Foundation for a yearlong project.

The research group plans to publish their findings and share them with the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services.

This article was produced by the Missouri Information Corps, a project of the Missouri School of Journalism. Have tips for us? Email: moinformationcorps@gmail.com.