In the days since George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police, crowds have gathered across the state and world to protest police brutality.

This has raised some concerns about worsening the spread of COVID-19. St. Louis County officials have asked unmasked protestors to quarantine for two weeks. Protests continued last week in Florissant against that police department after video showed an officer hitting a suspect with his SUV, then get out of the car and appear to strike him. The officer was fired.

“I don’t think that COVID-19 should be taken lightly,” said Robin Winn, an attorney and executive member of Columbia’s NAACP who helped organize a protest in downtown Columbia June 9. “But I think that protesting in this situation is actually going to save our lives.”

Winn, who has asthma, said she personally thought hard about attending a protest during the pandemic.

“I weighed that,” she said. “But this cause was so important to me that even I got out there.”

People who decided not to physically attend the protest donated supplies like water and first-aid kits, she said. Protest organizers helped distribute masks, encourage social distancing and provide legal knowledge about protesting.

Protesting police brutality in the middle of a pandemic is a nuanced public health issue, said Michelle Teti, associate department chair of public health at the University of Missouri.

Teti has spent the past 20 years studying health disparities in vulnerable communities.

“These are dual public health problems: racism and police violence against people of color and COVID,” she said.

Current data shows that COVID-19 is disproportionately hurting communities of color, Teti said.

“They are getting sicker and they’re dying at higher rates than white people,” she said.

Teti said people of color are at a higher risk for harm from COVID-19 because they are at higher risk for pre-existing conditions like asthma or heart disease, which can exacerbate COVID-19 symptoms.

She also pointed out that systemic racism is really at the root of the problem: Black people are disproportionately harmed by incarceration, which amplifies COVID-19 risk. And because of discrimination, people of color might lack access to health care or distrust health care establishments, Teti said. This could limit access to information and treatment, leading to worse outcomes.

But coronavirus doesn’t necessarily mean people shouldn’t protest, Teti said.

“People have the right to protest because racism and police violence damage people’s health, just like COVID does. Some people feel, understandably, that racism is a greater risk for their health and the health of their families. There are things that the police and the protesters can do to make those protests safe,” she said.

Police could make fewer arrests, limit corralling and wear proper personal protective equipment, Teti said. She also said officers should avoid using respiratory irritants like pepper spray that can increase coughing.

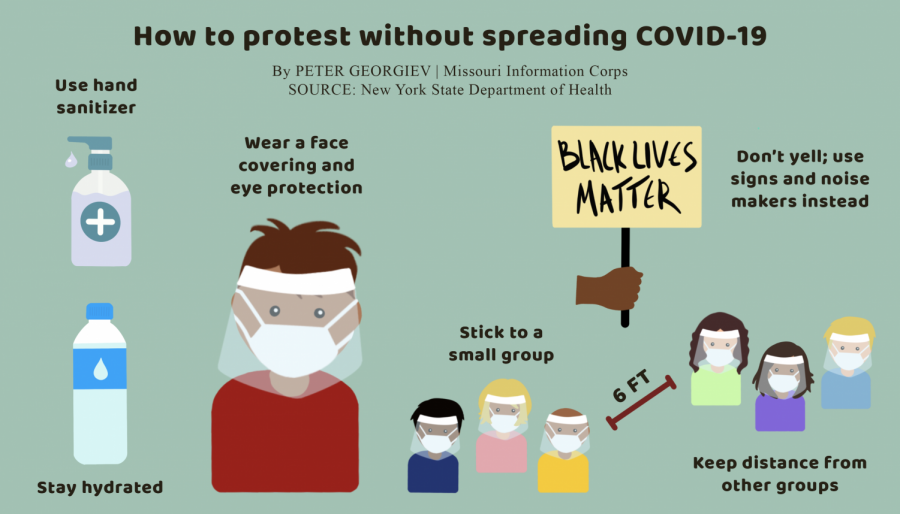

Protesters can protect themselves by not going out if they’re sick and by wearing masks. Teti also recommended using signs or noisemakers instead of shouting or chanting to limit the spread of germs. She said to stay 6 feet apart when possible.

Protest organizers are also taking the risks seriously.

Justice Horn, a Kansas City resident, helped organize two protests in the city, one June 10 and one June 12.

He said safety was a major concern.

“We’re all coming together to protest police brutality, but we don’t want to put anyone else’s life at risk,” he said.

Speaking after the first protest, Horn said masks were the norm. He said organizers asked protestors to monitor themselves for coronavirus symptoms for two weeks after attending a protest.

The American Civil Liberties Union has also provided basic resources and advice on how to protest safety.

“We encourage protesters to wear masks, bring hand sanitizer and practice social distancing,” said Danielle Spradley, communications associate for the Missouri Chapter of the ACLU.

Spradley pointed to information published on the national ACLU’s website, like a guide on protesting safely in a pandemic and a resource on personal rights while protesting police brutality.

This story was produced by the Missouri Information Corps, a project of the Missouri School of Journalism, sponsored by the Missouri Press Association. How has the pandemic changed life in your community? Email us your stories: moinformationcorps@gmail.com.