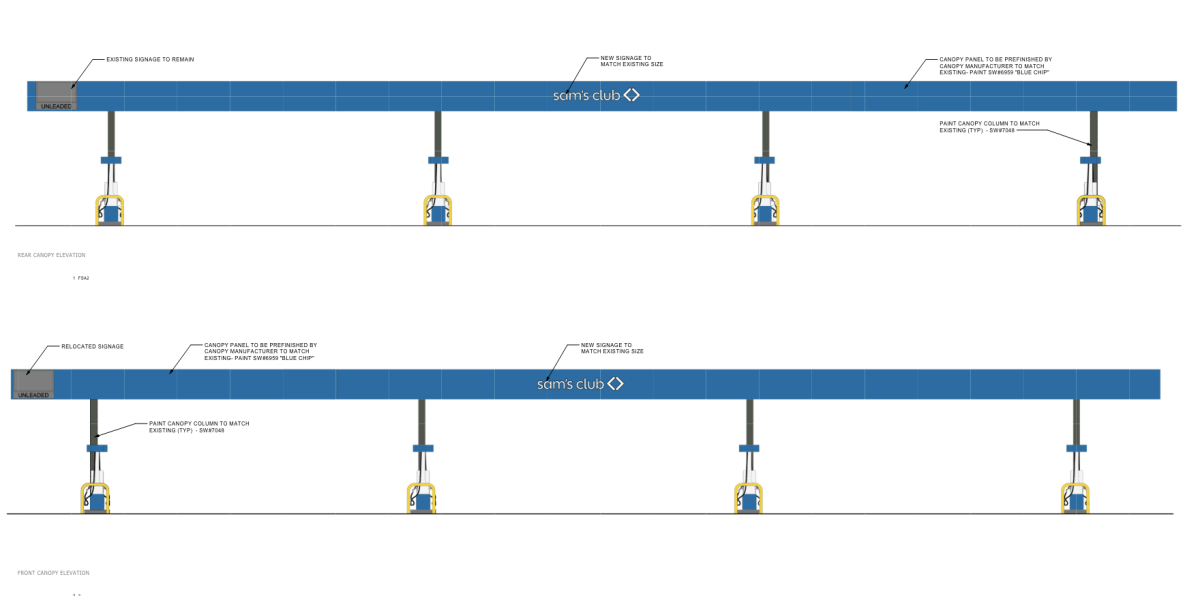

Pictured: The now-demolished Crestwood mall.

By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

news3@callnewspapers.com

UPDATE: House Bill 1236 passed out of the Local Government Committee Wednesday 8-2 and will go to a full vote of the House next week. Stay tuned for more in the April 26 print edition of the Call.

A bill that would give school districts a say in whether their property-tax revenues are diverted for tax incentives could be up for a key vote in the Missouri Legislature as early as this week.

House Bill 1236 would be the first major reform to state law governing tax-increment financing since state TIF laws first took effect decades ago.

If the bill is voted through the Rules Committee this week it could go to the full House for a vote, said Lindbergh Board of Education Treasurer Mike Tsichlis, who has shepherded the bill through the legislative process.

“This is a sea change in TIF law,” Tsichlis said. “We haven’t seen this kind of reform in TIF since TIF laws were established in the state of Missouri over 30 years ago. So it’s very significant. I’m amazed this bill made it this far.”

The bill would allow school districts and other taxing entities like fire districts to opt out of up to 50 percent of a TIF. It is heavily backed by Lindbergh Schools officials because it would help solve a conundrum around TIF: Currently a city or, if unincorporated, a county decides to grant a TIF. But most of the property taxes that are diverted to developers in TIF are from school districts, not cities. So a city is making decisions on tax revenue that isn’t its own.

One estimate by a Kansas City professor researching the impact of TIF found that each year, more than $100 million in tax revenue that would have otherwise gone to school districts throughout the state is diverted to TIFs. And unlike when money is diverted from city budgets for TIF, those school districts had no say in where that $100 million went.

The issue was illustrated locally when the Crestwood Board of Aldermen granted Chicago-based developer UrbanStreet Group $15 million in TIF for a proposed $104 million redevelopment of the former Crestwood Plaza mall that so far has stalled. Of that total, $9 million would have come from Lindbergh, not Crestwood. Lindbergh very publicly opposed the TIF because of UrbanStreet’s proposed residential housing, but despite funding most of the TIF, the school district only had two of the nine seats on the Crestwood TIF Commission. The seven representatives from the city and the county recommended the TIF over Lindbergh’s objections.

Lindbergh Superintendent Jim Simpson wrote to legislators that it often seems like those other seven members don’t “pay much attention to the proceedings since it is a foregone conclusion what the outcome will be.” That can be true of bills in the Legislature too, he added. It’s unusual for a completely new bill to come so close to a final vote, especially when the bill takes on so many entrenched interests.

“Experts, experts, a lot of people told Mike, ‘You’re never going to get the time of day over there,’” Simpson said. “I sort of thought that too. Because I’ve seen it fought and never get to first base over and over and over. The developer lobby is so strong, and cities themselves want the tool of giving the school tax dollars away.

“We’re the cash cow. They give us away and they give 60 cents out of every dollar away. All of a sudden we’ve got some serious millions on the table. So the cities don’t want to give it up at all. But he’s got it off the ground, and it’s actually in play. For the first time ever, TIF reform might happen.”

Of course, even if the bill makes it through the House and Senate, getting it signed by Gov. Eric Greitens could be a tough task given his legal issues and talk of impeachment. But during his campaign, Greitens came out against tax incentives for a new stadium in St. Louis.

To beat the odds, Tsichlis lobbied legislators and stayed on them to advance the bill. He testified at a March 14 hearing also attended by Lindbergh board member Christy Watz. Most of the testimony was supportive of the bill, but the Municipal League, the city of St. Louis and a Kansas City developer testified in opposition.

The bill’s success so far is even more remarkable since it is sponsored by a freshman legislator, Rep. Dan Stacy, R-Blue Springs. Support crosses party lines, and co-sponsors include one of Lindbergh’s legislators, Rep. David Gregory, R-Sunset Hills; Rep. Mary Nichols, D-Maryland Heights; and Rep. Rick Francis, R-Perryville, a retired Lindbergh assistant superintendent.

In the Senate, Sen. Andrew Koenig, R-Manchester, who represents Sunset Hills, sponsored companion legislation that redefines “blight,” which is required to grant TIF. That would make it more difficult to declare something blighted.

House leaders reconciled their bill with Koenig’s, which resulted in a compromise that backed down what school districts could opt out of from 100 percent to 50 percent. School districts would be able to hold their own separate hearing on TIF projects.

The change from a full opt-out to a partial opt-out gained some “yes” votes from legislators like Rep. Shamed Dogan, R-Ballwin, the chair of the Local Government Committee.

In essence, supporters of the bill are simply asking for a seat at the table when it comes to TIF to decide if a project is viable, Tsichlis said.

“That’s what we pushed when we were in Jeff City, and it was a difficult argument to be against,” Tsichlis said. “I literally asked them, ‘Who can be against more community voices?’ Dead silence in response. Who can say, ‘No, no, this isn’t something we advocate’? But they also fear that bringing more community voices in could change the nature of the outcome.”

In a letter to legislators, Simpson outlines the many failed TIF projects he’s seen in his three decades as an educator, primarily in other areas in Missouri. But in Crestwood, UrbanStreet has “left 47 acres of piles of unsightly dirt for over a year,” with plans on hold, Simpson wrote.

In one exceptional case, Lebanon actually turned down a TIF for a Walmart, only for one to be built in Lebanon anyway a few years later.

“The lesson I learned is the taxpayers of Lebanon, MO almost paid millions of dollars to one of the richest companies in the world when Walmart intended to put a store in Lebanon all along,” Simpson wrote.

When legislators first sold school districts on TIF legislation, they told a different story from how the law actually ended up being used today, Simpson said.

“I was in public education when TIF was born,” Simpson said. “I remember very well being at the meeting, the first one in Southwest Missouri, and the presenters came in and they used Times Beach, a toxic dioxin site in Jefferson County. Crossbones, nobody can go in. And they said this is what TIF is for — the toxic sites that every state has a few of. Never did they show us a mall, or retail.”