A federal judge has dismissed a lawsuit filed by a group of Christians alleging that St. Louis County’s stay-at-home order violates their religious freedom by banning large in-person church services.

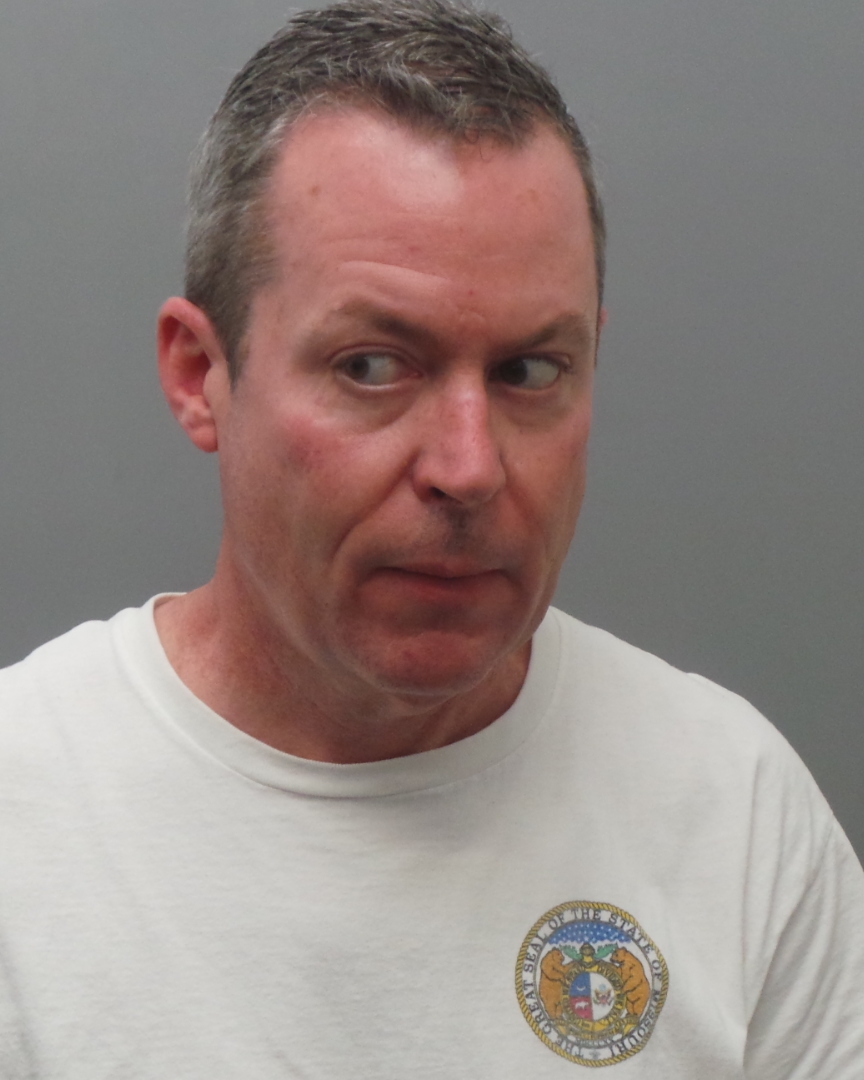

In the lawsuit filed April 28 and dismissed Sunday, St. Louis County residents Lauren Hawse, husband and wife Frank and Jean O’Brien and Stephen Pieper, a medical doctor, said that they have been unable to practice their religion since the stay-at-home order went into effect in March for the coronavirus pandemic.

They believe the “draconian” stay-at-home order violates their freedom of religion protected by the First Amendment.

But U.S. District Judge Ronnie White, an appointee of President Barack Obama, dismissed the lawsuit Sunday for lack of standing after lawyers for St. Louis County filed a motion to dismiss arguing that the group of Christians did not state in their lawsuit that the county lockdown was what was keeping their churches from opening, or why not being able to attend church in person would prevent them from practicing their religion.

The group of Christians filed a notice of appeal.

Clayton attorney Michael Quinlan represents the Christians and alleged in the lawsuit that the stay-at-home order issued by County Executive Sam Page “prohibits plaintiffs’ free exercise of religion by banning religious services attended by more than 10 persons while permitting all manner of secular and commercial activities without similar restrictions.” But the county’s attorneys argued, and White agreed, that the county’s order did not specifically prohibit religious gatherings: It prohibits all gatherings of more than 10 people.

In the suit, Quinlan noted that the stay-at-home order allows big-box stores to stay open with no crowd size restrictions, along with other areas where crowds could gather such as public transportation. But even though churches are classified alongside those stores as “essential” businesses under the order, the limits on crowd sizes apply to churches but not the stores. The attorney said that discriminates against churches.

“There is no rational basis — and certainly no empirical data — to conclude that there is less likelihood of COVID-19 spread among Walmart shoppers, for example, than among church goers who observe the same social distancing and other hygienic precautions,” Quinlan said in the suit. “Upon its face, therefore, the Order discriminates on the basis of religion, tacitly deeming — despite their ‘essential’ designation — that religious activities are, to invert the dictum of Orwell’s pigs, ‘less essential than others.’”

One of the St. Louis County residents bringing the suit, Frank O’Brien of O’Brien Industrial Holdings, previously sued the Obama administration because he said that the requirement that companies provide health insurance that covers birth control violated his religious beliefs. He was also part of a lawsuit that challenged the St. Louis Board of Aldermen’s decision to make the city a “sanctuary city” for abortion.

White did not dismiss one of the claims by the group, which alleged that the county’s order violates the due-process clause of the 14th Amendment because it “effectively places plaintiffs under house arrest unless they are engaged in activity the government deems ‘essential.’”

A similar claim in another federal lawsuit was preliminarily denied Friday by U.S. District Judge Stephen R. Clark, an appointee of President Donald Trump. A county gym owner has also sued the county in circuit court to overturn the order and allow businesses to reopen.

Although Quinlan said that his clients’ ability to attend church on Sundays “is an essential requirement of their sincerely held religious belief,” White sided with county attorneys who argued that Quinlan did not point out how attending church in person is an integral part of those beliefs that could not be accomplished at home.

To satisfy the “standing” requirement of federal courts, plaintiffs must show that they suffered directly due to the defendant’s action and that if they prevailed in the lawsuit, their grievance would be solved. But White said that there is no evidence that church services will resume as normal even after the St. Louis Archdiocese allows local churches to make that decision as the county stay-at-home order begins to lift May 18.

White said that the group of Christians did not identify their specific churches or whether they are closed specifically because of the county’s mandate and would reopen if the county mandate ended.

“Plaintiffs do not allege that their large church gatherings were suspended because they were unlawful under the Order, rather than in response to the general COVID-19 public health crisis,” White wrote. “Notably, Plaintiffs’ affidavits in support of the Complaint are devoid of any facts concerning these issues whatsoever…. Thus, based upon the Complaint, the Court is unable to discern the specific impetus for closure of Plaintiffs’ churches and, likewise, what would enable their churches to reopen.”

In a reply to the county’s motion to dismiss, Quinlan said his clients weren’t required to provide specifics about their religious beliefs or churches because the order banned all religious gatherings, not those from a specific denomination.

Since the order bans all gatherings above 10 people, religious services of fewer than nine people would still be allowed, the judge said: “The Order does not impose a categorical bar on Plaintiffs’ worship at church.”

The judge continued, “Plaintiffs’ Opposition misses the mark… The Court does not question whether Plaintiffs have a sincerely held religious belief. Rather, the Court questions the proximate cause of the churches’ closings and whether it has the ability to remedy Plaintiffs’ alleged injury.”