By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

glorialloyd@callnewspapers.com

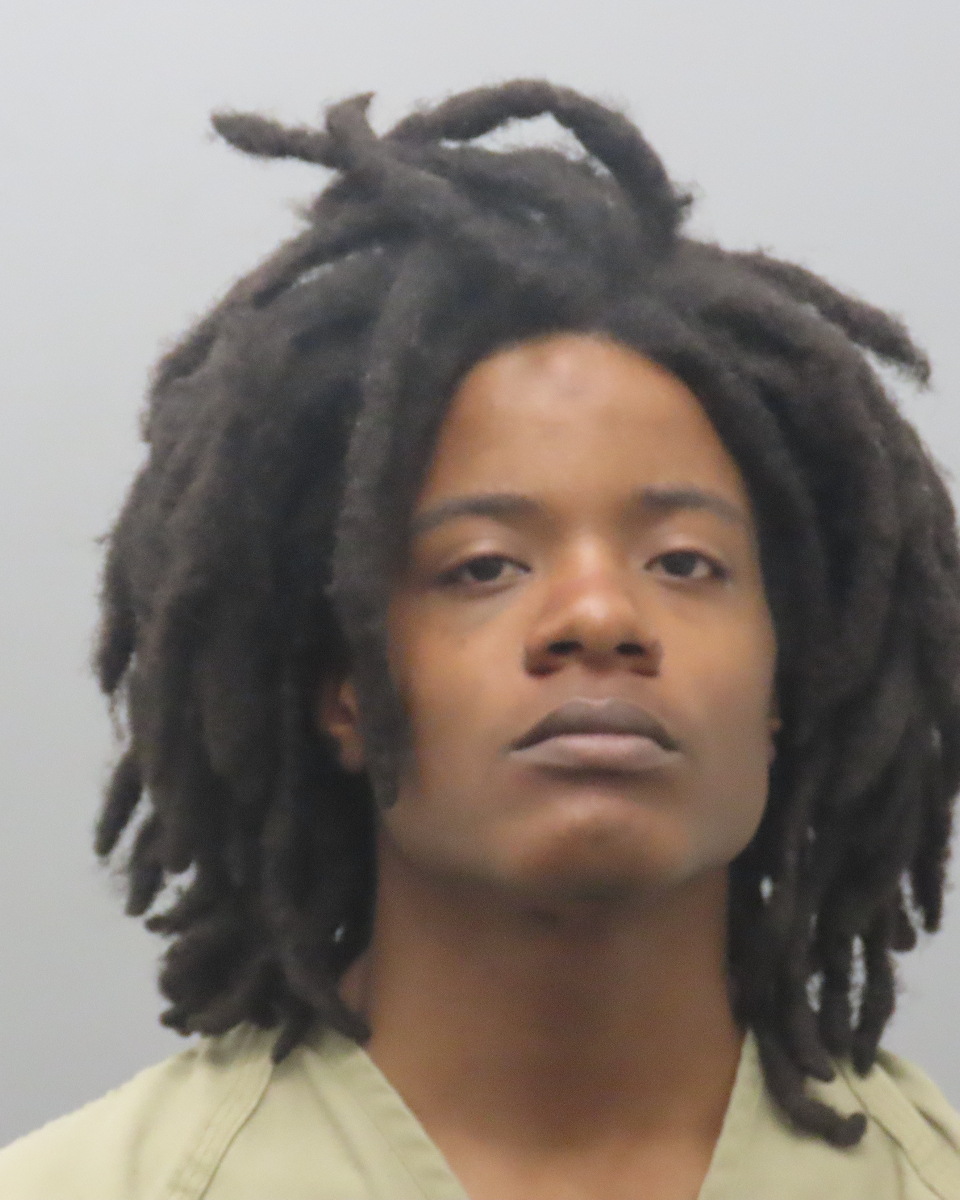

He called it “the art of staying in power,” but Bill Miller, who served as chief of staff to former St. Louis County Executive Steve Stenger, could face prison time after pleading guilty Friday in Stenger’s sweeping pay-to-play corruption scheme exchanging county contracts for campaign donations.

William “Bill” Miller Jr., 54, of Richmond Heights, pleaded guilty at the Thomas F. Eagleton U.S. Courthouse in downtown St. Louis to one felony count of aiding and abetting honest services wire fraud/bribery — the three things Stenger pleaded guilty to May 3. Miller “defrauded the citizens of St. Louis County,” according to his plea deal.

Represented by attorney Larry Hale, Miller is the third person to plead guilty in the scheme including Stenger, and federal prosecutors said their investigation that started in March 2018 is still “active and ongoing.”

Miller will be sentenced Sept. 6. Hale declined to comment on Miller’s behalf.

An attorney and former newspaper publisher who served as Stenger’s right-hand man alongside Stenger’s former Chief of Policy Jeff Wagener, Miller ran the day-to-day operations of county government from the time Stenger hired him in December 2017 to his resignation April 12, when he released a statement that his departure had already been in the works for months.

To the public, Miller was Stenger’s bulldog, attacking the County Council during last year’s budget negotiations when Stenger declined to get involved. Miller issued a statement for Stenger calling the council’s millions of dollars in cuts a “breach of public trust.”

But behind the scenes, prosecutors say he was the one violating the public trust. In conversations that appear to have been captured through a wire worn by Wagener, Miller often served as the enforcer behind Stenger’s sweeping scheme to grant county contracts and land deals to campaign donors.

The businessman who benefited from several of those deals, John Rallo, faces the same charges as Stenger and pleaded not guilty, and former St. Louis Economic Development Partnership CEO Sheila Sweeney pleaded guilty to misprision of a felony for concealing Stenger’s crimes.

Stenger directed many of the contracts he wanted to award to donors through Sweeney, who led the joint city-county economic agency and the county Port Authority as its executive director. He appointed Miller to the Economic Partnership’s board in 2018, along with Wagener.

Throughout 2018, Miller was the “muscle” behind pressuring Sweeney to award those contracts, according to Stenger’s 44-page indictment.

“In taking such official action in aid of Stenger’s criminal scheme, Miller deprived the citizens of St. Louis County of their right to his honest services as the county’s chief of staff and as a member of the board of the St. Louis Economic Development Partnership,” the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Missouri said.

In an application for a search warrant on Stenger’s iPhone, an FBI agent quoted a private conversation between Miller and Stenger at Stenger’s house last fall in which Miller said he would take care of what the FBI agent classified as a “bribe” of a County Council member. Stenger told Miller he would handle it himself.

But none of those conversations factored into Miller’s plea deal, in which he agreed to plead guilty in exchange for prosecutors agreeing not to bring any other charges. His pact with prosecutors only mentions the $200,000 annual Bardgett lobbying contract, which the Economic Partnership canceled May 22. Bardgett had donated a total of $59,000 to Stenger over the years.

He could face prison time for the single count of corruption, however: Under federal sentencing guidelines, prosecutors and his lawyers listed him as a 14, which could amount to 15 to 21 months in prison for a first-time offender. The single corruption count could carry a sentence of up to 20 years and a $250,000 fine, and a judge is not bound by prosecutor recommendations.

Prosecutors and Hale agreed to a base level of 7 for the offense, but added multiple levels because the money involved was more than $95,000 and because Miller “abused a position of public trust.” Three levels were deducted for his decision to plead guilty.

In comparison, Stenger was listed as a 21 under federal sentencing guidelines and prosecutors recommend he serve three to four years in prison, while Sweeney was a 9 or 10 and could face four to 12 months in prison.

In another conversation with Wagener quoted verbatim in Stenger’s indictment, Miller talks about Stenger wanting him to go to Sweeney’s office and “throw her down in a wrestling move” because she was apparently resisting Stenger’s wish that she award a contract to one of his donors, lobbyist John Bardgett of John Bardgett & Associates.

Miller thought Stenger’s method was “overkill,” but he told Wagener, “I don’t know, Jeff, I think it’s risky… If it was just me and her, in some dark room somewhere, I might make it a little bit more forceful.”

Speaking to Miller, Stenger said to tell Sweeney that if she didn’t give the contract to Bardgett’s firm he would fire her. They were both political people, and she should know that, he said.

“It’s the art of staying in power,” Miller replied.

Miller was close enough to Stenger that he held Stenger’s son Lincoln at the county executive’s victory party in August. But he was also sometimes the target of Stenger’s ire. An FBI agent wrote in an affidavit to a judge asking for the phone search warrant that on a day last fall leading up to the November general election, Stenger stopped going to work altogether. When Miller went to Stenger’s house in Clayton to ask him about some county business, Stenger yelled at him that he was busy dealing with donors. The entire exchange was caught on FBI wiretaps.

The chief of staff announced he was resigning April 12, but said the move had been planned with Stenger since 2018 and that he originally only planned to stay on through Stenger’s re-election before agreeing to extend his time in the office.

Miller said at the time of his resignation, “I informed County Executive Stenger several months ago that I would be resigning as his chief of staff in order to pursue other employment opportunities. I’m grateful to have worked in this administration alongside so many dedicated public servants.”

Miller’s since-deleted online resume stated that he was the “chief operating officer responsible for executive staff and management of all aspects of St. Louis County government, including a county budget of $664 million with more than 4,000 employees.”

Before taking the position with Stenger in December 2017, Miller served as a state-appointed administrative law judge from January 2017 to June 2017 and acting policy director for former Gov. Jay Nixon from May 2015 to January 2017.

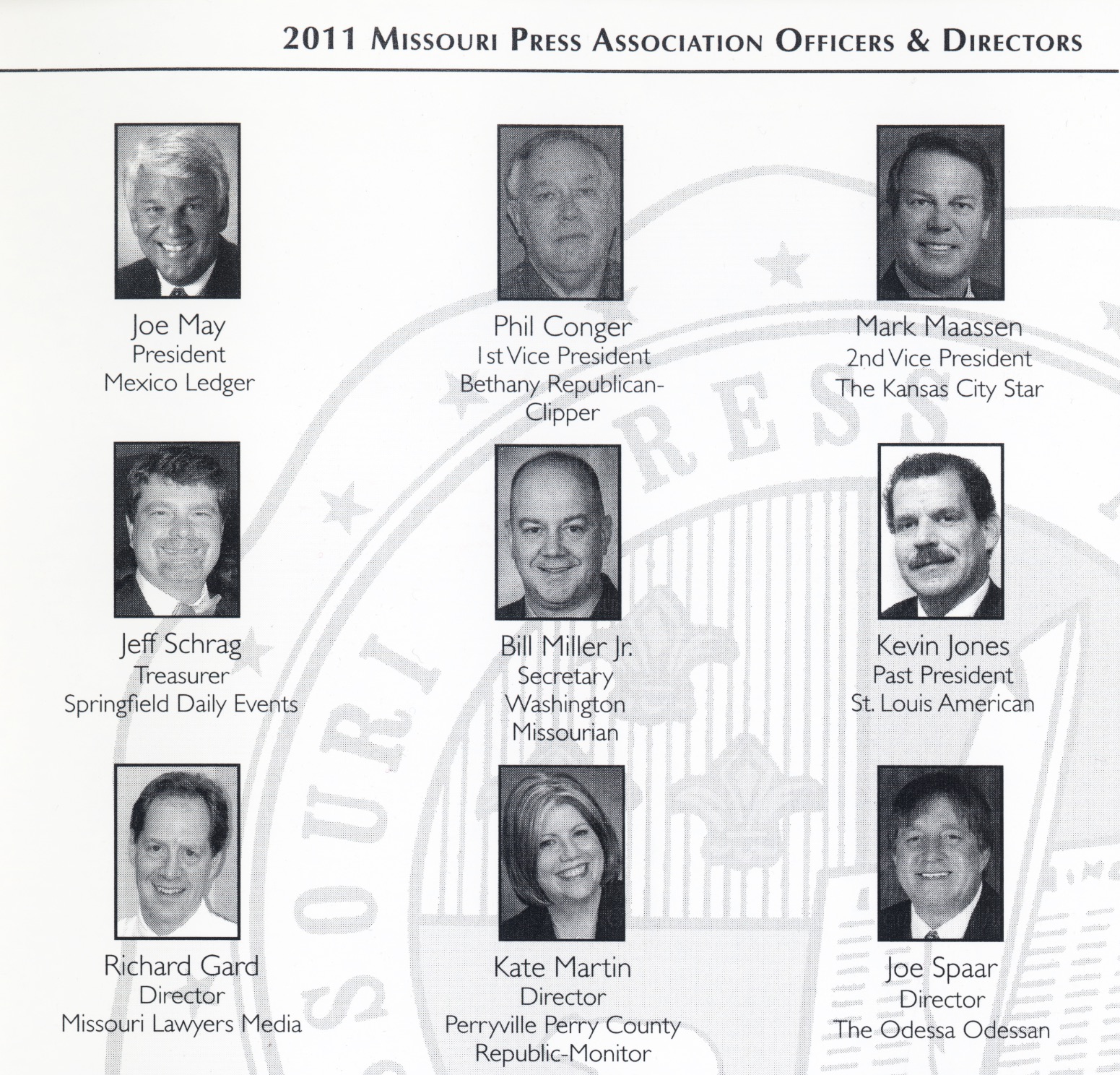

He was the owner of his family’s Washington, Missouri-based newspaper company Missourian Publishing from 1996 to May 2015, according to his online resume. During that time, he served on the board of the Missouri Press Association.

Miller still serves as the vice president and on the board of Missourian Publishing, according to business filings. His father, Bill Miller Sr., is the editor, publisher and president of The Missourian.

In the past, Miller has even covered crime and sentencing for The Missourian.

An attorney, Miller went to law school at St. Louis University, just as Stenger did.

Read the plea deal below: