By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

glorialloyd@callnewspapers.com

Prosecutors in the trial of a man accused of killing a St. Louis County police officer from the Affton Southwest Precinct are making the argument that Officer Blake Snyder’s murder happened from Trenton Forster’s choices, not mental illness.

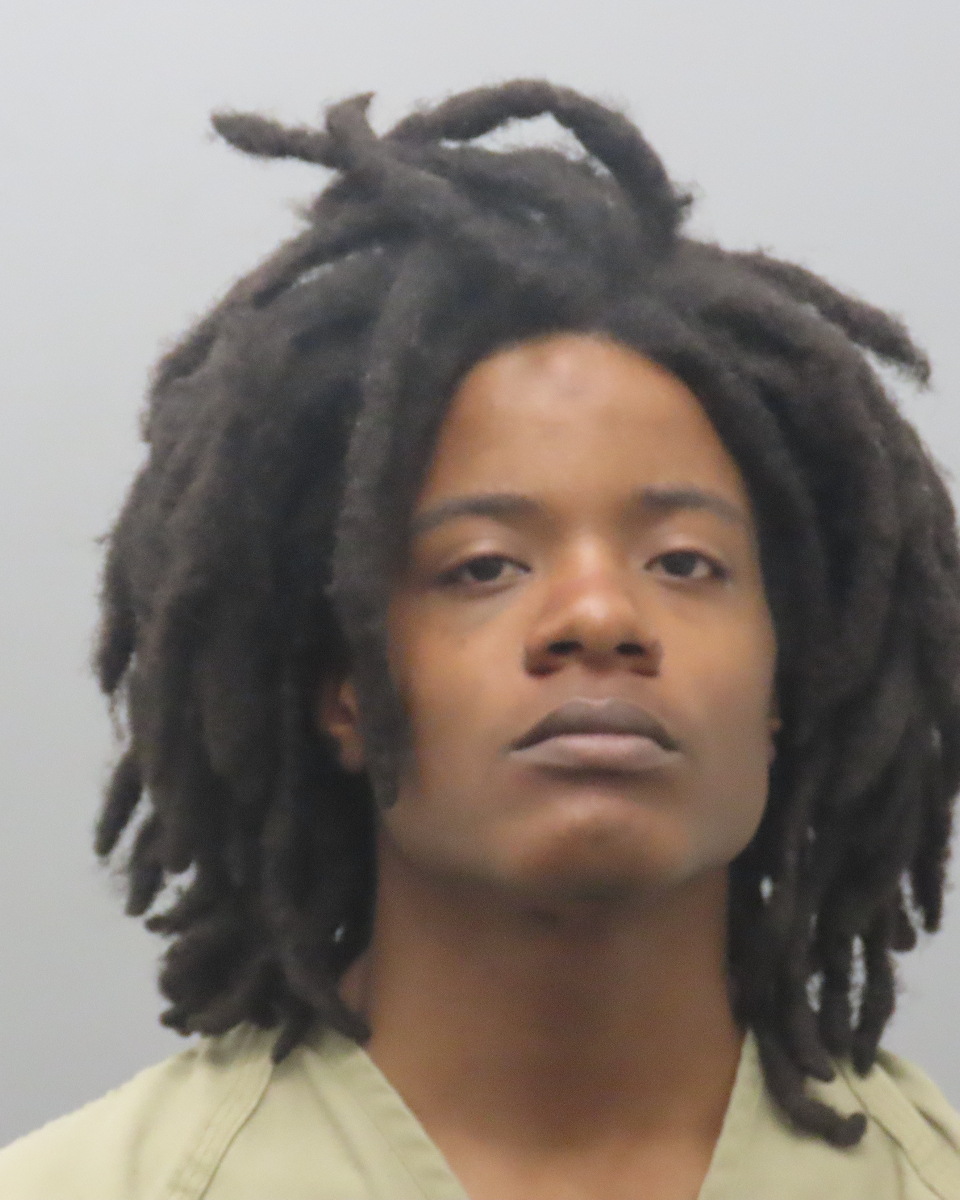

Jurors could come to a decision as soon as Friday on whether to convict Trenton Forster, 20, of first-degree murder or second-degree murder for shooting and killing Officer Blake Snyder Oct. 6, 2016.

And that decision hinges on whether they believe that he intended to kill Snyder that night or did it in the spur of the moment due to what a psychiatrist called a manic episode from bipolar depression.

The officer’s widow, Elizabeth Snyder, is calling for a huge turnout for closing arguments Friday in an expanded overflow room from police officers throughout the region. St. Louis County officers, many of them from the 3rd Precinct, have crowded into an overflow room for the five-day trial and lined the hallways of the courthouse for support.

Closing arguments are set to start Friday morning, after which the jury will go into deliberation.

Snyder, 33, a four-year veteran of the St. Louis County Police Department’s Affton Southwest Precinct, was almost immediately shot to death by Forster while responding to a call for a domestic disturbance in the 10700 block of Arno Drive in Green Park at 5:04 a.m. Oct 6, 2016.

And the events on Arno Drive were the tragic end to several frenetic days of pivotal events, jurors heard Wednesday and Thursday in testimony from Forster’s family, friends and strangers who encountered him.

In the days leading up to the morning he killed a police officer, Forster was binging on drugs after just receiving $9,000 in an insurance settlement from a car crash and desperate to get a gun because he felt that someone was after him, according to numerous accounts given from the witness stand. Using the same money, he had also just bought the car he used to drive to the scene.

Forster’s public defender Stephen Reynolds is not contesting Forster’s guilt, but argues that he should be convicted of second-degree murder, which would carry a chance of parole, instead of first-degree murder, which would be an automatic life sentence with no parole. Former county Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch decided not to pursue the death penalty in the case.

A forensic psychologist paid $35,000 so far by Forster’s defense, Patricia Zapf, said that the night of the murder Forster was in the throes of mania from the bipolar depression he’d suffered from all his life, and was still dealing with trauma from a troubled childhood filled with thoughts of suicide and drug use. She said he was just reacting to instinct when he shot Snyder, rather than making a conscious decision to kill a police officer.

But the three assistant county prosecutors trying the case — Alan Key, David Hasegawa and Jason Denney, a Crestwood resident who also serves as the city’s municipal judge — argue that Forster made a series of fateful decisions in the days leading up to the shooting and, as numerous social media postings indicate, specifically wanted to kill a police officer or die by “suicide by cop.” They emphasized in their questions on cross-examination the various choices he made, the chances he had to reform himself and his conscious decision not to follow any rules but his own.

In testimony Thursday, his father, William “Bill” Forster, and mother, Christina Forster, recounted how he was unusual even as a child.

Growing up in Hannibal, Trenton Forster “took things to extremes,” his father said, both good and bad. He was an excellent athlete, but when he got into an argument with someone over something inconsequential like a video game, “it would erupt into chaos.”

At first, the family dismissed the temper tantrums as normal childhood behavior, but they got worse as he got older.

Forster had irrational fears that led him to sleep in the walk-in closet of his brother Brandon, who is four years older than Trenton, for more than a year. He slept there long enough that he even hung posters on the walls as if it was his room, William Forster said.

The problems were compounded by William Forster’s opiate addiction, which happened around the time Trenton was 9 and 10 years old, and the parents’ very contentious divorce, which happened around the time Trenton was 11.

Christina Forster rated the bitter divorce as a “10 out of 10” on the level of acrimony and said it was followed by a bitter three-year custody battle in which a judge ultimately awarded custody to her ex-husband.

During the divorce, his mother packed up the children and took them to Tennessee to see her family, but in Forster’s mind, his mother “kidnapped” him and he still characterizes it as that type of trauma to this day, the psychologist said. The child “screamed from St. Louis to Nashville” and the incident became a “turning point in his life,” his father testified.

Christina Forster said her son always had an unusual attachment to his father and always wanted to be “attached at the hip” to him, to the point of not going on family vacations or going into panic attacks when he couldn’t do what he wanted. For a year, she said Bill Forster set up his bed in Trenton’s room.

The father admitted on the stand that Trenton was his favorite child and that he favored him over his older son. But still, the pair had a destructive relationship at times, with the father at one point giving his middle-school-age son drugs and drug paraphernalia, Zapf said. She said Bill Forster denied those allegations.

Trenton Forster was injured in a car crash when he was 13 and after that, seemed to spiral into more of a depression, family members said. He had threatened to kill himself from a young age, but that increased after the crash, his mother testified. His father says he remembers the talk of suicide starting after the crash.

From a young age, Forster abused substance after substance, from alcohol as a seventh-grader to harder drugs like opiates and Xanax soon after.

He got a few fresh starts along the way that seemed to make things better for a time, his family testified, including moving to St. Louis from Hannibal in June 2013; moving into his aunt’s house in the summer of 2015; switching from Lindbergh High School to Affton High School in fall 2015; and finally, living in Tennessee in the summer of 2016.

Each time, his new life started out promising. But then he quickly turned to his same old ways after he got back in with his old friends or made new friends that revolved around drugs.

His father wanted to move him to St. Louis so that he could get away from a drug-centered social life in Hannibal like his brother had experienced, but instead, Trenton Forster found the “wrong crowd” at Lindbergh High School and from then on, his life revolved around drugs.

When he admitted to his father that he had been taking Oxycontin, Bill Forster tried to have him committed to an inpatient rehab/mental health facility, but he only stayed for a week and then refused to comply with the outpatient treatment he was supposed to have after discharge. Approaching his 16th birthday, he asked his father if he could smoke marijuana one last time on his birthday. When his father said no, Forster ran away.

Officer Jeremy Hake, now the Green Park officer, responded to Bill Forster’s call for a crisis-intervention team and took Trenton Forster back to the inpatient program, the officer testified Thursday.

Forster stayed in rehab for 50 days, but “came home unrehabilitated,” his father testified. It was the summer between his freshman and sophomore years at Lindbergh High School.

Nearly every day, he continued making suicidal statements. When his father said he was going to take away his cell phone, Bill Forster testified that his soon looked at him with “stone cold eyes” and said, “I’m going to kill myself this weekend, and it’s going to be your fault.”

His father called police, who took him to Mercy, where Forster was discharged with the promise that he would complete outpatient treatment. He refused to go the next day, so his father called police again, who put him into an inpatient psychiatric unit at Mercy.

When Forster’s father caught him stealing from his stepsister’s purse in April 2016, the father told his son that when he turned 18 in June he’d have to find a new place to live.

And after Forster turned 18, his family couldn’t legally make him do anything.

By the time he shot Snyder, Forster was essentially homeless and in what Zapf called a “downward spiral” that began when he returned from Tennessee about a month before.

But Key fought against the idea that Forster was in a helpless situation, noting that he had multiple relatives who took him in at various times and sent him for treatment multiple times: “He’s not some kid, some orphan, on the street that never had any family to help him.”

Forster had always battled drug and mental-health problems, but in September 2016 he had $9,000 in hand from a settlement from the car crash that had happened when he was 13. His mother drove him to get the money, reasoning that he was 18 and would get it anyway. Then she went back to Tennessee.

“Everybody else in the family has testified today he was in the throes of a major drug addiction, and you dropped him off with $9,000 cash?” Key asked incredulously.

Another time, Key called that decision a “death sentence” for anyone with drug addiction.

The cash spurred a monthlong drug binge and all-out efforts to get a gun, pestering family members, friends and strangers that he needed to get a gun because someone was out to get him. He ended up buying two guns, the handgun used to kill Snyder and a long shotgun that was made to look like an AK-47 that he kept in his trunk.

His grandmother testified she told him to use the money to get an apartment, but he didn’t want to.

He told his father that “when the money was going to run out, he was going to run out,” meaning kill himself or overdose on drugs, William Forster testified.

At a meeting a few days before the encounter with Snyder, Forster told his father that he had managed to buy a gun.

“I told him nobody wins in a gun fight,” the father said.

Testimony Wednesday detailed Forster’s single-minded intent to buy a gun in the days leading up to the murder. He ended up buying one from a man he met at Sunshine Daydream for $550. He was turned away from Mid-America Arms in Affton three times because he looked high.

The man who ultimately sold him the gun testified that Forster was “chomping at the bit” to get his hands on a gun, supposedly for self-defense.

The night of Snyder’s murder Oct. 6, Forster was going around to family members and acquaintances begging them to spend the night. But they had all been burned too many times and turned him away, one after the other.

Forster went to the back patio of his father’s house in Concord about 2 p.m. Oct. 5 begging to spend the night, slurring his words and nearly falling asleep standing up.

Bill Forster said his son was “incoherent” and refused to let him in the house: “He was so high he couldn’t speak.”

It was the last time he saw his son before he was charged with first-degree murder.

“I’ll never forget, as he he drove away, he gave me the peace sign and drove down the street,” Bill Forster said.

That night, the elder Forster called Officer John Becker, an acquaintance of a neighbor who along with Snyder was the responding officer to the scene the next morning and ended up shooting Trenton Forster five times. Becker had also arrested Forster the year before.

But the night before, Bill Forster said he asked Becker what to do about his son, who was “depressed and high.” He said he was afraid he would hit someone with his car while under the influence.

“I told him ‘I’d really love you guys to pick Trenton up,’” Bill Forster testified.

When Becker told him the police could only intervene if he was a danger to himself and others, Bill Forster said his son fit that category.

On cross-examination, Key aggressively questioned why Bill Forster didn’t take away his son’s keys or tell Becker that Trenton had a gun.

“Were you drunk or high or what?” Key asked.

Bill Forster said he wasn’t sure if he told Becker that his son had a gun.

“You didn’t, because they wouldn’t have walked up to your son’s car if you had,” Key yelled. “We wouldn’t be here if you said, ‘He’s dangerous, he’s suicidal and he’s got a gun.’”