By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

glorialloyd@callnewspapers.com

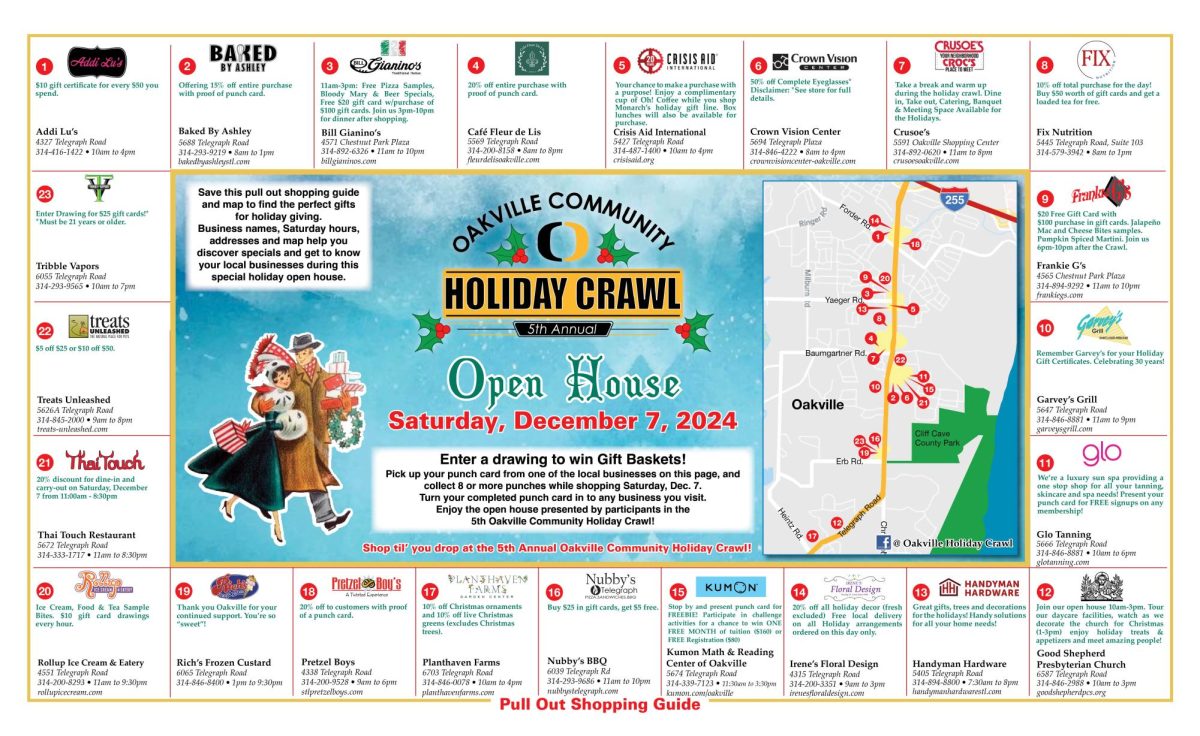

If voters across Missouri agree, all of St. Louis County and city could be consolidated by 2022 into one large “metro city” under a single government – including one mayor, council and police department – that backers say will save money and create a better business climate that will set the region up to thrive rather than fall behind.

The plan that nonprofit organization Better Together released Monday addresses crime, overspending, fragmented government and abusive city practices while keeping the aspects of local municipalities that residents enjoy most, supporters of the proposal say. Critics say it is a misguided plan for “UniGov” that has to be sent to a statewide vote because local residents would never go for it.

Under the plan, St. Louis County and city would become one government, population 1.3 million, in the same style adopted by Louisville, Kentucky; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Nashville, Tennessee. Voters statewide will consider it in November 2020 as an amendment to the Missouri Constitution, pending a petition drive that would be largely funded by billionaire megadonor Rex Sinquefield.

Supporters of the initiative have lofty goals, as summed up by County Executive Steve Stenger in the event announcing the campaign rollout Monday at the Cheshire Inn — chosen because it symbolically straddles the city and county line. He and St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson support the plan.

“I envision a more prosperous life for generations of St. Louisans, a life that is driven by transformational and fundamental change, powered by unity and sustained economic growth and the vitality offered by a new city moving forward under one government, with one unified vision,” Stenger said.

Key powers of cities like Crestwood and Sunset Hills would be taken away, including policing, zoning and the ability to collect most sales tax. But the cities could stay around as “municipal districts” that shift their funding to property taxes instead of sales taxes to provide services like trash, recycling, parks and fire departments.

The plan was developed by a five-member task force that includes Oakville resident Arindam Kar, an attorney at Bryan Cave who, like many of the speakers at the rollout, emphasized the need to fix the problem of two St. Louises, with the “haves” and the “have-nots.”

“There are real human costs to the St. Louis we’ve created,” Kar said, later adding, “Folks must hold this new government, once it’s created, accountable for the changes.”

The specter of Better Together’s statewide vote on a plan had the cities that are members of the Municipal League of Metro St. Louis adopting an alternative way to come up with a plan last week, through the Board of Freeholders process outlined in the state Constitution.

Critics have long called the idea of such a city-county merger a bailout for the city of St. Louis, which has roughly $600 million in outstanding debts that has some contending the city is on the verge of bankruptcy.

But Better Together backers maintain the plan would not be a bailout in two ways: The city earnings tax would continue for 10 years and pay down the bond debt. And in the same vein as smaller municipalities like Green Park and Grantwood Village, the city of St. Louis would be covered as a “municipal district” that would have special taxing power to continue existing taxes, at least for awhile, that would also pay off its debt and pension obligations so that other residents of the new city wouldn’t have to.

‘Metro mayor,’ 33-member council would govern

The plan is backed by the region’s major business interests. Stenger and others have questioned why St. Louis’ growth seems to be stalling while Louisville, Nashville and Indianapolis are “thriving,” and they believe it relates directly to having a more centralized government.

That would create efficiencies, both money-wise and with zoning and policing, said Better Together Director of Community Studies Dave Leipholtz, a graduate of Lindbergh High School. A Better Together study found that the region overpays for government compared to those other cities by $750 million to $1 billion each year.

Even with adding hundreds of millions of dollars to the new police force to increase officers on the street, the new St. Louis metro city would immediately save the area’s taxpayers $250 million a year for local services, he said.

The county currently has 52 police forces, most of them set up by municipalities in north county. That damages efforts by larger departments like the St. Louis County Police Department to track and solve crime locally, as many of those departments don’t communicate. Outside organizations like newspapers have said they’ve had difficulty getting regional crime statistics because some departments refuse to release crime data publicly.

The move would also help economic development by removing the city of St. Louis from its current perch atop many national crime rankings. That’s a misleading figure because most other cities have their suburban areas included in their rankings, and the FBI statistics are calculated by dividing crime by square miles.

Immediately, St. Louis would go from appearing to be at the top of crime rankings to down in the 30s or 40s, while also going from the 20th or so largest city to the ninth largest, just behind Dallas, Texas. Businesses have said that crime rankings are the first thing they look at when deciding where to locate.

But Better Together says crime would also be better addressed by one department with high standards.

Vote to happen statewide

The nonprofit organization says that a vote has to happen statewide because the plan would change not just the aspects of the Constitution directly related to St. Louis county and city governance, but other aspects that, as one key example, require cities of over 400 people to either directly provide or contract for police service.

Leipholtz said that even an enabling vote, in which statewide voters would approve constitutional changes pending a positive vote locally, would violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which says that no one’s vote should be worth more than someone else’s. That approach could be challenged in court, he said.

But asking voters in Poplar Bluff whether to create a new government in St. Louis strikes many as unfair.

“I’d be strongly opposed to that,” Crestwood Mayor Grant Mabie said. “From the feedback I’m getting in the community, there are frankly a pretty big divergence of opinions about the merits of regional cooperation, merger… But the one unifying trait among people all across the spectrum is that from a procedural standpoint, everyone agrees that it’s really the right thing to do to have the consent of the governed. It’s a hallmark of American democracy. To have someone outside your region control your form of government isn’t democracy, and it isn’t appealing.”