By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

glorialloyd@callnewspapers.com

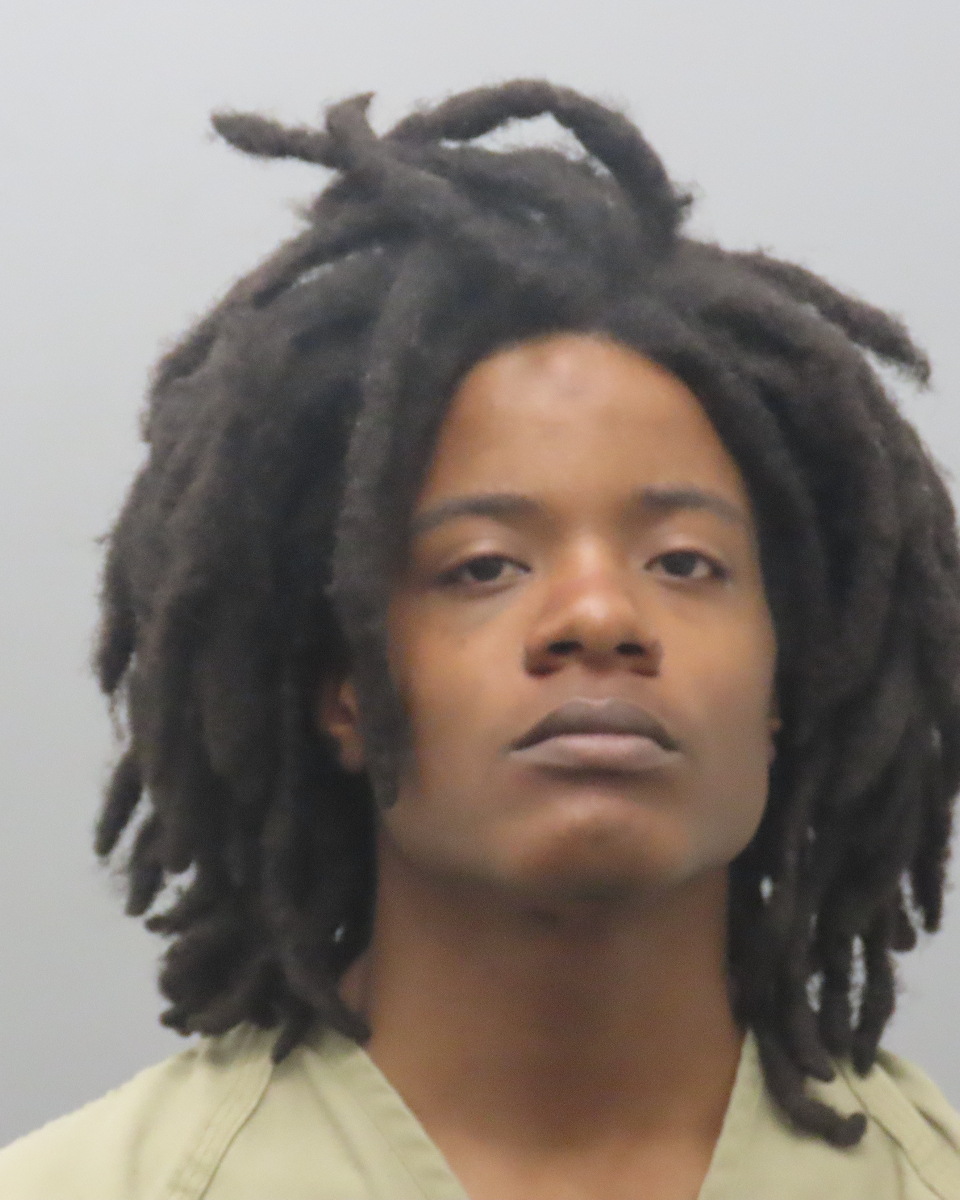

The trial of the south county man who admits he shot and killed Officer Blake Snyder is underway in Clayton this week, and with Trenton Forster’s guilt not up for debate, most of the courtroom testimony centers around whether a St. Louis County jury should convict the 20-year-old of first-degree murder or second-degree.

Final arguments are set to begin Friday, after which jurors go into deliberations. It would be the fifth day of an expected five-day trial.

Officer Blake Snyder, 33, a four-year veteran of the St. Louis County Police Department’s Affton Southwest Precinct, was almost immediately shot to death by Forster while responding to a call for a domestic disturbance in the 10700 block of Arno Drive in Green Park at 5:04 a.m. Oct 6, 2016.

Testimony from the Mehlville Fire Protection firefighter-medic who treated Forster’s shooting wounds the morning he killed Snyder indicated that Forster, then 18 years old, was having second thoughts in the minutes after the killing.

Lying on a stretcher bleeding from his own wounds, he said, “If I’d have known he was a cop, I wouldn’t’ve shot him. He snuck up on me,” according to testimony Thursday from Heather Herbold, a firefighter-medic who worked for the Mehlville Fire Protection District at that time and now works for the Valley Park Fire Protection District.

Opening testimony and evidence presented the basic facts of the case in the first two days of the trial: Forster, the subject of the disturbance call, was sitting in his car on the street after banging on the back patio of his friend’s house on Arno Drive, demanding to be let in.

Officer John Becker responded to the scene at the same time as Snyder. Becker, who had once arrested Forster for drugs, testified that he recognized the teenager and slowly drove by his car, parking in front of Forster and rolling down his window to hear the exchange with Snyder.

Snyder pulled up behind Forster and approached Forster’s white Chevy Monte Carlo saying, “Hey bud” and “Let me see your hands,” county Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Alan Key said.

Using a handgun he had just bought, Forster shot and killed Snyder, then, still sitting in the driver’s seat of his car, pointed his gun at Becker. Becker shot him five times, bullets piercing the headrest. Forster screamed, “Shoot me, shoot me, kill me, kill me,” Key said.

It was a rare murder on the quiet suburban streets of Green Park, and the first county police officer to die in the line of duty in nearly two decades.

And the events on Arno Drive were the tragic end to several frenetic days of pivotal events, jurors heard Wednesday and Thursday in testimony from Forster’s family, friends and strangers who encountered him.

In the days leading up to the morning he killed a police officer, Forster was binging on drugs after just receiving $9,000 in an insurance settlement from a car crash and desperate to get a gun because he felt that someone was after him, according to numerous accounts given from the witness stand.

Forster’s public defender Stephen Reynolds is not contesting Forster’s guilt, but argues in a “diminished capacity” defense that his client should be convicted of second-degree murder, which would carry a chance of parole, instead of first-degree murder, which would be an automatic life sentence with no parole. Former county Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch decided not to pursue the death penalty in the case.

But the three assistant county prosecutors trying the case — Key, David Hasegawa and Jason Denney, a Crestwood resident who also serves as the city’s municipal judge — argue that Forster made a series of terrible decisions in the days leading up to the shooting and, as numerous social media postings indicate, specifically hoped to kill a police officer or die by “suicide by cop.” They emphasized in their questions on cross-examination the various choices he made, the chances he had to reform himself and his conscious decision not to follow any rules but his own.

A forensic psychologist funded by Forster’s defense said that the night of the murder Forster was in the throes of mania from the bipolar depression he’d suffered all his life, and was still dealing with trauma from a troubled childhood.

She testified that Forster was not in control of his actions that day, basing her assessment on four full days of interviews with him, extensive interviews with his family and medical records dating back to his childhood documenting his long history of mental illness and drug abuse.

“He’s all over the place, agitated, not thinking of the consequences, reflexively reacting,” Zapf said. “Emotion is high, thinking is low.”

In his manic state, Forster believed that people were after him, which was why he said he needed to buy the gun and hounded family members, friends and strangers to see if he could buy a gun until a man he met at Sunshine Daydream finally sold him one.

In his heightened manic state, shooting Snyder was an “instinctive reaction,” Zapf said.

She said Forster told her in her interview with him that when he realized that he’d shot a police officer, he had a moment of reflection on what he did after he raised the gun again and before Becker shot him.

“He’s confused, he’s disoriented, there’s chaos going on,” Zapf testified. “It’s not that he’s snapped out of manic, it’s that he’s all of a sudden realized what he had done. So he’s now sort of coming to and realizing the gravity of the situation.”

But Key countered, “Wouldn’t you agree that pointing a gun at an officer is not terminating the attack? He didn’t drop the gun and say, ‘I’m sorry.’… Wouldn’t you think murdering a police officer and then turning a gun on another officer — why wouldn’t that be suicide by cop?”

The first ambulance to the scene took Snyder to Mercy Hospital South, then St. Anthony’s Medical Center, followed by a parade of police cars from multiple jurisdictions.

Herbold arrived on the second ambulance to care for Forster, who was lying on the street handcuffed next to a pool of Snyder’s blood, screaming in pain.

After Forster stopped screaming in the ambulance, he said he was dying. Herbold testified she held his hand and assured him on the ride to Mercy Hospital St. Louis, “I’m not going to let you die.”

She said she asked him, “Why did you have a gun? You’re 18 years old.”

At that, “he turned away and wouldn’t talk to me,” Herbold said.