Neither the Lindbergh nor Mehlville school district met Adequate Yearly Progress requirements for the last academic year, but that doesn’t alarm the districts’ su-perintendents.

AYP reports track whether Missouri school districts will comply with 2002’s No Child Left Behind Act. Districts have until 2014 to make sure each student is proficient in reading and math, according to the federal mandate.

Because states are allowed to create their own definition of what proficiency means, Missouri set its requirements based on the Missouri Assessment Program tests, which students take every spring. Based on a five-level system, students must score at above grade level, which is the second highest, to be considered proficient.

The Missouri Department of Secondary and Elementary Education last week released AYP reports.

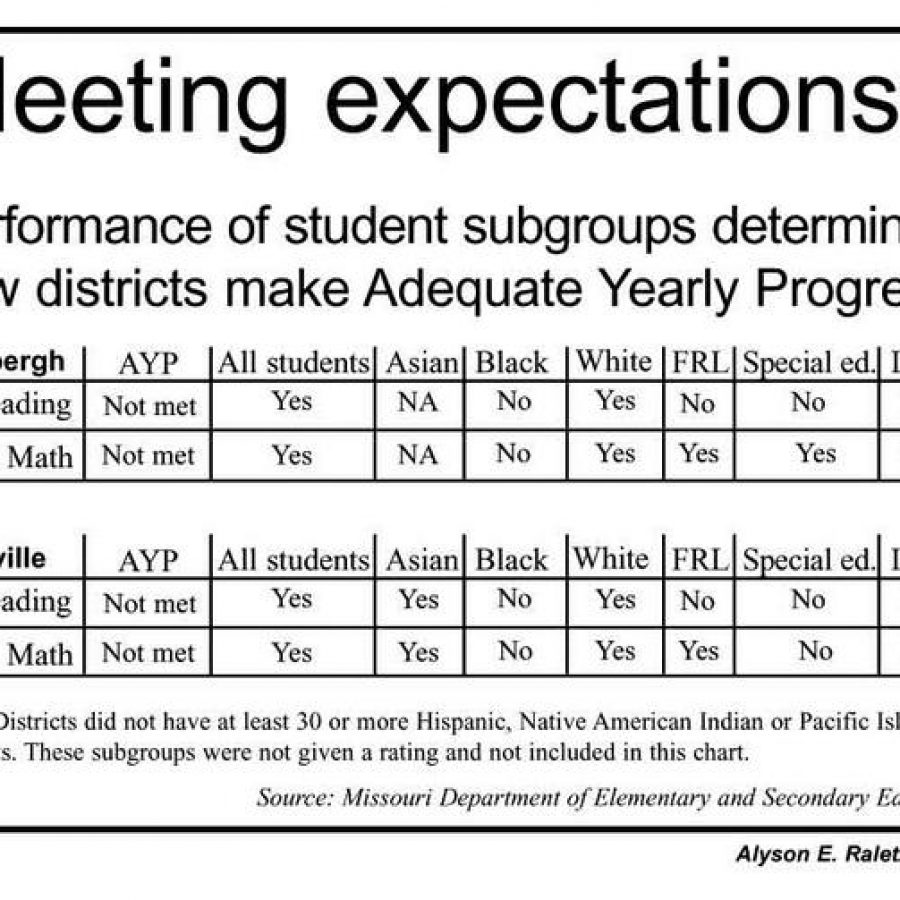

The Lindbergh and Mehlville school district superintendents learned the majority of their students had shown AYP, but they still were designated “not-met” districts because certain subgroups of students did not show AYP.

In the eyes of state and federal government, students are divided into 10 subgroups. Student subgroups include special education, free/reduced lunch, limited English proficiency, white, black, Asian, Hispanic, Native American Indian, Pacific Islander and other/non-response.

Only districts that have each subgroup of students performing at proficiency levels in math and reading are designated “met” districts. If one subgroup does not show AYP in either math or reading, then a district is designated “not met.”

But Lindbergh Superintendent Jim Sandfort said the AYP report for his district is great news.

“These results are an indication that the majority of our students are reaching and exceeding benchmarks, but we still have some challenges,” Sandfort said.

The only subgroup at Lindbergh that showed proficiency in both math and reading was the group of white students. Free and reduced lunch, black and special education students did not show AYP in reading. In math, the only subgroup that did not show AYP was the black student group.

The case is similar in Mehlville as it also was designated a “not-met” school district.

Asian and white students showed AYP in math and reading assessments. Black, special education and limited English proficiency students did not show AYP in math or reading. Students in the free or reduced lunch program at Mehlville did not perform at proficiency levels in reading, but they did so in math.

Both superintendents contend the Missouri proficiency standards are higher than other states, which makes the inconsistency hard to compare Missouri with other parts of the country.

Also, both district leaders described their districts as more diverse than other districts in the state and nation that met AYP requirements.

Sandfort attributes more rural districts receiving “met” ratings to having a higher concentration of white students. In many cases, he said, there are not sufficient numbers of minority students to create a subgroup.

Mehlville Superintendent Tim Ricker said it is difficult to compare 12,000 diverse suburban students with more “homogeneous” student bodies.

“Painting with a broad brush is not equitable,” Ricker said.

This is the first year the state produced AYP numbers and sent them to districts.

Sandfort said despite his district’s “not- met” rating, he believed the data was helpful.

“With the newness of legislation and the complexity of the rating structure, no one was really sure what to expect,” he said. “The fact that the subgroups for the white population were ranked as having met the requirements was a reaffirmation that Lind-bergh programs are quality programs.”

The black achievement gap is an area the district was working on for many years be-fore the No Child Left Behind Act became effective, he said. Lindbergh continues to provide special education and work with children who have difficulties with learning.

Even though minority subgroups did not meet government standards, he said those groups improved and have had some success — just not enough success to reach the threshold of standards set by the federal government.

“Folks have to realize that these are federal mandates, not additional federal dollars,” Sandfort said.

Ricker said the AYP data for Mehlville is a good baseline of information and it helps the district identify children who are not doing well, but the report revealed no surprises — it’s all information district officials have known for a long time.

“Is there any data we didn’t know about? No,” Ricker said. “We’re not going to panic. We’re not behind an eight ball in any shape or form.”

The district has been addressing the specific needs of its black and special education students along with its growing Bosnian population and the needs of its children with a low socioeconomic status, he said.

Staff members at each school in the district have been formulating improvement plans that specifically deal with these concerns.

Ricker said the district is up for continued improvement, but these efforts would have taken place with or without the AYP reports.

“We would do this anyway,” he said.

The superintendents said the AYP scores do not show the full story, particularly given the fact that both districts last year earned the Missouri Department of Ele-mentary and Secondary Education’s Distinction in Performance Award.

The Distinction in Performance recognition is awarded to school districts based on criteria established by the Missouri Board of Education, including MAP test scores, ACT test scores, attendance and dropout rates and other indicators of academic success.

Lindbergh and Mehlville graduation rates and ACT scores both are higher than national averages.

Ricker said Mehlville is showing im-provement despite its “not-met” rating.

Five years ago, the district performed poorly on its Missouri School Improvement Program evaluation, but earlier this year it received 148 of 149 possible points for its MSIP evaluation. Public school districts undergo MSIP evaluations every five years to earn their accreditation classification based on three sets of standards — resource standards, process standards and performance standards. To earn full accred-itation, a school district must receive 106 of the possible 149 points.

“There’s an incongruence here,” Ricker said. “People would die to have our numbers. I am proud of our district.”