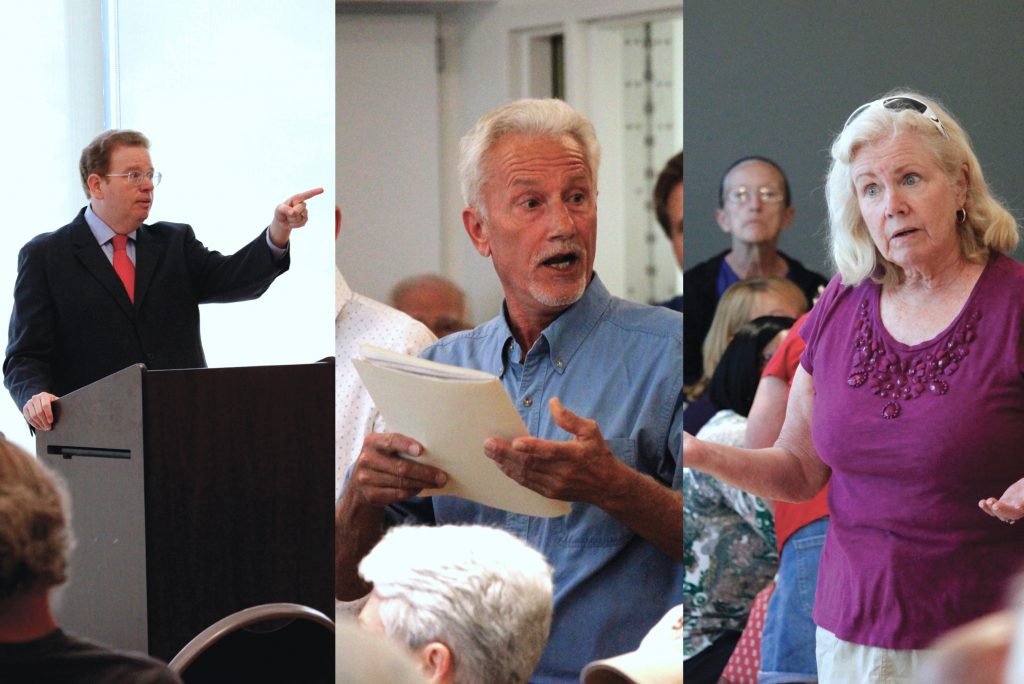

Jake Zimmerman, left, takes questions about this year’s property value reassessments from residents during a town hall at The Pavilion at Lemay June 20. Residents unhappy with the jump in values include Doug Brunkhorst of Oakville, middle, and Penny Kelly of Crestwood, right. Photos by Erin Achenbach.

By Gloria Lloyd

News Editor

glorialloyd@callnewspapers.com

St. Louis County’s highest increase in property values in over a decade has some residents angry because they feel they’ll have to unfairly pay higher taxes.

Rising property values were on the minds of at least a hundred people who attended a town hall with St. Louis County Assessor Jake Zimmerman last week at The Pavilion in Lemay. The sometimes-contentious crowd posed questions to Zimmerman and sometimes confronted him over what they saw as inexcusable behavior from his team of assessors who meet in person with residents who appeal.

“We’re upset and irate,” said Oakville resident Douglas Brunkhorst, who repeatedly interrupted the meeting to confront Zimmerman.

The town hall was co-hosted by County Council Presiding Officer Ernie Trakas, R-Oakville, and 5th District Councilwoman Lisa Clancy, D-Maplewood.

Property values rose by double digits in nearly every corner of St. Louis County, topped by 34 percent in the Hancock Place School District and averaging 17 percent in Lindbergh Schools and 15 percent in the Mehlville School District.

Taxpayers have until July 8 to submit their appeals in writing, but time is running out to make appointments to meet with assessors in person to protest the assessed valuation. That deadline looms July 1.

Until then, residents can meet with an assessor, who can change the valuation or keep it the same. The resident can then appeal to a Board of Equalization hearing officer, then the full Board of Equalization, then the state Tax Commission. After that they would need to hire an attorney, which isn’t feasible for most homeowners.

Zimmerman, a Democrat who took office in 2011 as St. Louis County’s first elected assessor, said he would hear everyone’s concerns, even if “you just want to tell me I’m a jerk.”

Reassessment happens every two years under Missouri law. The skyrocketing home values seen in current assessments are the “best news for the real-estate market” that Zimmerman said he’s seen since going into office. And unlike past years where home values in Clayton and Ladue may have surged, this year is seeing increases from Lemay to North County.

“In every neighborhood in St. Louis County, the typical property is worth more than it used to be worth,” he said.

He said that due to an abundance of young families buying their first houses and property flippers buying modest homes to tear down and rebuild, the dirt that homes sit on is worth more now than it was two years ago.

Some senior citizens at the town hall yelled out that they’ll never sell their homes, so they don’t care about selling prices. Zimmerman said that the Missouri Legislature has failed to pass bills that could give them tax relief and freeze their property taxes, as is done in other states.

One of the homeowners who said she’d welcome any such help was Penny Kelly of Crestwood. Her house itself actually went down in value from two years ago, $156,800 to $142,000, but the land under her house increased in value from $53,000 then to $95,000 now, according to the assessor’s office. Her total assessed valuation went up from $209,000 to $236,900, nearly what it was worth in 2008 before the Great Recession sent prices downward.

“You made a comment that you were looking to help seniors,” Kelly told Zimmerman. “I am a senior, I am a widow, I’m on a fixed income. My property value went up over 50 percent, and I’ve got all kinds of issues to deal with. I have an older home, it’s 73 years old, so I have all sorts of things, like cracked driveways and patios and mold in the basement. If you’re working on this — is it going to be too late?”

The taxes she pays to Lindbergh were estimated to go up by $1,000 next year.

The assessor noted that while his office controls assessments, it doesn’t control the tax rates set by school and fire districts, which are where most residents send most of their tax dollars. And even if someone’s property values went up significantly, they may not pay more in taxes because under Missouri’s Hancock Amendment, tax rates have to be rolled back so that governments can’t take a windfall of extra money due to higher assessments.

Some people’s assessments will be lower than average and some will be higher, but if their assessment doesn’t exceed the average, they generally won’t pay higher taxes and could even pay lower taxes.

“If the values go up, they have to lower them right back down,” Zimmerman said. “Even if your house goes up 20 percent, most people’s taxes don’t change.”

He said that assessors use a computerized program, followed by actual human to human checking to ensure accuracy, on the 400,000 properties in the county: “My only job is to value your property based on what it could sell for” as of Jan. 1, he said.

But sometimes assessors make mistakes, like calculating the wrong number of bathrooms or whether a basement is finished or unfinished. Zimmerman encouraged residents with any question about their assessed value to talk to his assessors, who were at the town hall, and bring photos, comparable sales, estimates for home repair work that the homeowner can’t afford to do and other proof that the house could not sell today for what it’s assessed for. Examples of things that could affect home value are mold in the basement, a leaky roof, or a $20,000 plumbing issue.

But Zimmerman and the taxpayers who came to confront him had two very different ideas of what the appeal process is like.

The assessor described it as a professional meeting with a full-time assessor with a “green eyeshade” who isn’t a politician and doesn’t care about tax bills or anything beyond strict accuracy in property values.

He estimated that one in three people who appeal get the issue solved at that in-person meeting. They will meet with 20,000 residents over two months, he said.

But some residents in attendance said they had been insulted or dismissed by the in-person assessors. They described steep increases in taxes they felt were unjustified, and said they can’t afford them.

Webster Groves resident Heather Todd said her assessment came back $100,000 above what a realtor said she could sell her house for a year ago. She said she bickered “back and forth like a used-car salesman” with her assessor, before he finally said, “My manager won’t let me adjust it.”

She told Zimmerman, “If the process doesn’t work, then it’s not legitimate. Everyone’s getting angry, and no one can believe the process.”

Zimmerman was troubled about the feedback on the assessors and asked anyone who had a bad experience to give the details to his customer service manager.

“We’re the government, we’re not going to be perfect,” he said at one point, but he said the process should be better for residents.